Aesop

Aesop[1†]

Aesop[1†]Aesop (Greek: Αἴσωπος, Aísōpos; c. 620–564 BCE) was an ancient fabulist and storyteller credited with a number of fables now collectively known as Aesop’s Fables[1†]. Although his existence remains unclear and no writings by him survive, numerous tales credited to him were gathered across the centuries and in many languages in a storytelling tradition that continues to this day[1†]. Many of the tales associated with him are characterized by anthropomorphic animal characters[1†].

Early Years and Education

Aesop’s early life and education are shrouded in mystery, with various sources providing conflicting accounts. He is believed to have been born around 620 BCE[1†][2†]. The earliest Greek sources, including Aristotle, suggest that Aesop was born in the Greek colony of Mesembria[1†]. However, later Roman writers, including Phaedrus who adapted the fables into Latin, claim that he was born in Phrygia[1†]. Other sources propose that he was from Thrace[1†][3†], or even Ethiopia[1†][4†].

Aesop is universally acknowledged to have been a slave[1†][4†][1†][2†][5†]. He served two masters in succession, both of whom were inhabitants of Samos[1†][2†][5†]. His first master was a man named Xanthus, and his second master was a man named Iadmon[1†][5†]. Aesop must eventually have been freed, as he is later recorded as conducting the public defense of a wealthy Samian[1†][5†]. This freedom was possibly granted by his second master, Jadmon, as a reward for his learning and wit[1†][2†][5†].

Despite the lack of concrete details about Aesop’s early years and education, it is clear that he was a man of great learning and wit, qualities that would have been nurtured and developed during his formative years[1†][4†][1†][2†][5†].

Career Development and Achievements

Aesop’s career is as much a mystery as his early life, with various sources providing different accounts. Despite his status as a slave, Aesop appears to have worked as a kind of personal secretary to his master and to have enjoyed a great deal of freedom[3†]. His reputation derived from his skill at telling fables as illustrations of points in argument, possibly even in court[3†].

Aesop is remembered for some of the most popular fables ever written, broadly known as ‘Aesop’s Fables’[3†][6†]. Most of these stories have anthropomorphic characters and have a moral attached to them[3†][6†]. However, it is wise to remember that his stories were compiled by others throughout history[3†][6†]. There is no actual evidence whether or not he told these stories[3†][6†]. Similar fables have been found in other ancient cultures as well[3†][6†].

The moral animal fables associated with him were probably collected from many sources, and initially communicated orally[3†][7†]. They were later popularized by the Roman poet Phaedrus, who translated some of them into Latin[3†][7†]. The first known collection of the fables ascribed to Aesop was produced by Demetrius Phalareus in the 4th century BCE, but it did not survive beyond the 9th century CE[3†][4†]. A collection of fables that relied heavily on the Aesop corpus was that of Phaedrus, which was produced at Rome in the 1st century CE[3†][4†].

Aesop’s fables have survived centuries because of their simplicity[3†][6†]. They have remained relatable throughout time and history and have been used to teach moral values to children[3†][6†]. Some of the most popular fables are ‘The Ant and the Grasshopper’, ‘The Boy Who Cried Wolf’, and ‘The Crow and the Pitcher’[3†][6†]. Additionally, morals like “birds of a feather flock together”, “necessity is the mother of invention”, and “slow but steady wins the race” are also ascribed to him[3†][6†].

First Publication of His Main Works

Aesop is credited with a number of fables now collectively known as Aesop’s Fables[1†]. These fables, characterized by anthropomorphic animal characters, have been gathered across the centuries and in many languages in a storytelling tradition that continues to this day[1†]. Although no writings by Aesop himself survive, his tales have been adapted and retold by numerous authors throughout history[1†].

Here are some of his main works:

- "The Ant and the Grasshopper"[1†][5†]

- "The Bear and the Travellers"[1†][5†]

- "The Boy Who Cried Wolf"[1†][5†]

- "The Boy Who Was Vain"[1†][5†]

- "The Cat and the Mice"[1†][5†]

- "The Cock and the Jewel"[1†][5†]

- "The Crow and the Pitcher"[1†][5†]

- "The Deer without a Heart"[1†][5†]

Each of these fables carries a moral lesson, and they have been used for teaching ethics and values from ancient times to the present day[1†]. The importance of these fables lies not so much in the story told as in the moral derived from it[1†][4†].

The first known collection of the fables ascribed to Aesop was produced by Demetrius Phalareus in the 4th century BCE, but it did not survive beyond the 9th century CE[1†][4†]. A collection of fables that relied heavily on the Aesop corpus was that of Phaedrus, which was produced at Rome in the 1st century CE[1†][4†]. Phaedrus’s treatment of them greatly influenced the way in which they were used by later writers, notably by the 17th-century French poet and fabulist Jean de La Fontaine[1†][4†].

Analysis and Evaluation

Aesop’s fables have been analyzed and evaluated by scholars, educators, and critics throughout history. His works are characterized by their brevity, their focus on animals and inanimate objects, and their moral or philosophical themes. The fables often end with a moral, which is intended to illustrate a particular virtue or life lesson.

The impact of Aesop’s fables on literature and education has been profound. His fables have been used as a teaching tool for children for centuries, helping to instill important moral lessons and values. The stories have been translated into multiple languages and adapted into various forms, including plays, films, and animated features.

Critics have praised Aesop’s fables for their timeless wisdom and relevance. The themes explored in his fables, such as honesty, kindness, and perseverance, are universal and continue to resonate with readers today. His fables have also been analyzed for their use of irony and satire, and for their insights into human nature.

Despite the enduring popularity of Aesop’s fables, some critics have pointed out that the stories can sometimes reinforce societal norms and values that may be outdated or problematic. However, many agree that the fables’ enduring appeal lies in their ability to provoke thought and discussion about moral and ethical issues.

Personal Life

Aesop’s personal life is shrouded in mystery, much like his existence. The earliest Greek sources, including Aristotle, indicate that Aesop was born around 620 BCE in the Greek colony of Mesembria[1†]. However, a number of later writers from the Roman imperial period say that he was born in Phrygia[1†]. The 3rd-century poet Callimachus called him “Aesop of Sardis,” and the later writer Maximus of Tyre called him "the sage of Lydia"[1†].

By Aristotle and Herodotus, we are told that Aesop was a slave in Samos; that his slave masters were first a man named Xanthus, and then a man named Iadmon; that he must eventually have been freed, since he argued as an advocate for a wealthy Samian[1†]. Plutarch tells us that Aesop came to Delphi on a diplomatic mission from King Croesus of Lydia, that he insulted the Delphians, that he was sentenced to death on a trumped-up charge of temple theft, and that he was thrown from a cliff[1†].

Before this fatal episode, Aesop met with Periander of Corinth, where Plutarch has him dining with the Seven Sages of Greece and sitting beside his friend Solon, whom he had met in Sardis[1†]. According to Herodotus, Aesop was a companion of the beautiful courtesan Rhodopis, about 2600 years ago[1†][8†].

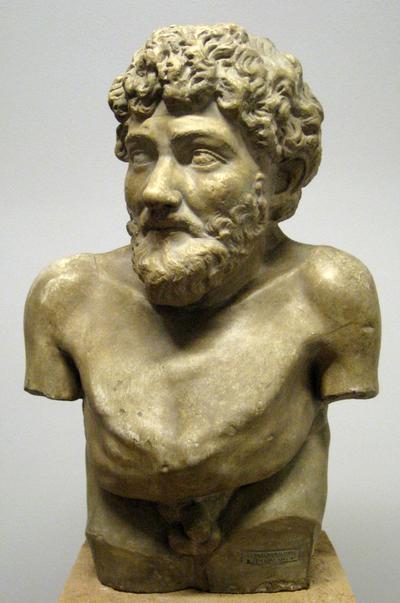

Aesop is depicted in many historical sources as being ugly, grotesquely figured, with an oversized head[1†][6†]. Spanish painter Diego Velázquez paints him as a philosopher with no deformities[1†][6†]. He has been similarly painted by Jusepe de Ribera, in ‘Aesop, poet of the fables’ and ‘Aesop in beggar’s rags’[1†][6†].

Conclusion and Legacy

Aesop’s fables have become an integral part of the heritage of Western literature and folklore[3†]. His life story reinforces a significant theme in the fables: that of being unable to change one’s nature and status[3†][9†]. Although he succeeds for a time, his destruction ultimately comes as a result of these changes[3†][9†].

Aesop was apparently so talented at recounting fables that memorable examples became attached to his name, regardless of their origin or date[3†]. Thanks to later writers who collected them, these fables have become an integral part of the heritage of Western literature and folklore[3†].

The importance of fables lay not so much in the story told as in the moral derived from it[3†][4†]. The first known collection of the fables ascribed to Aesop was produced by Demetrius Phalareus in the 4th century BCE, but it did not survive beyond the 9th century CE[3†][4†]. A collection of fables that relied heavily on the Aesop corpus was that of Phaedrus, which was produced at Rome in the 1st century CE[3†][4†]. Phaedrus’s treatment of them greatly influenced the way in which they were used by later writers, notably by the 17th-century French poet and fabulist Jean de La Fontaine[3†][4†].

Aesop’s fables have had a profound impact on literature and storytelling, with the name Aesop becoming synonymous with fables[3†][10†]. His fables have been adapted and translated into many languages and have influenced a wide range of writers and philosophers[3†][4†][10†].

Key Information

- Also Known As: Esopo, Aesop is also known by the Greek name Αἴσωπος (Aísōpos)[4†].

- Born: The exact date of Aesop’s birth is uncertain, but it is estimated to be around 620 BCE[4†].

- Died: The date of Aesop’s death is also uncertain, but it is generally believed to have occurred around 564 BCE[4†].

- Nationality: Aesop’s nationality is a subject of debate. Some sources suggest that he was born in Thrace, while others propose that he was a Phrygian or an Ethiopian[4†]. He is also said to have lived on the island of Samos[4†].

- Occupation: Aesop is best known as a fabulist or storyteller[4†].

- Notable Works: Aesop’s most notable works are the fables that are attributed to him, collectively known as Aesop’s Fables[4†].

- Notable Achievements: Aesop’s fables have had a profound impact on literature and storytelling. His fables, known for their moral lessons, have been adapted and interpreted in various forms and media, influencing a wide range of artistic and literary works[4†].

References and Citations:

- Wikipedia (English) - Aesop [website] - link

- Litscape.com - Life of Aesop, Aesop [website] - link

- eNotes - Aesop Biography [website] - link

- Britannica - Aesop: legendary Greek fabulist [website] - link

- ancient-literature.com - Classical Literature - AESOP [website] - link

- The Famous People - Aesop Biography [website] - link

- Encyclopedia.com - Aesop [website] - link

- University of Illinois - Rare Book and Manuscript Library - Wise Animals: Aesop’s Life and Legend [website] - link

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy and its Authors - Aesop’s Fables [website] - link

- The Collector - Who Was Aesop? (5 Facts About the Greek Fablist) [website] - link

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; additional terms may apply.

Ondertexts® is a registered trademark of Ondertexts Foundation, a non-profit organization.