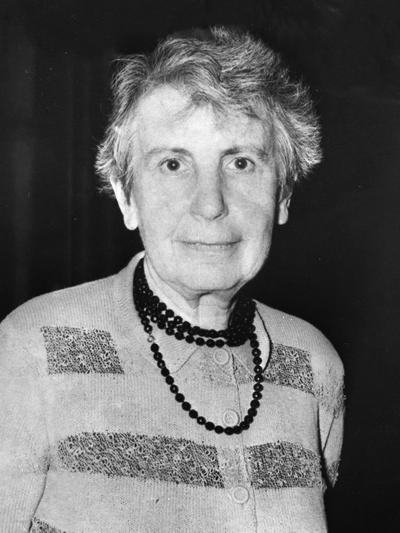

Anna Freud

Anna Freud[1†]

Anna Freud[1†]Anna Freud (3 December 1895 – 9 October 1982), born in Vienna to Sigmund Freud, became a pioneering British psychoanalyst of Austrian-Jewish heritage. Known for her contributions to psychoanalytic child psychology, she emphasized the normal development of the ego and co-founded the field alongside Hermine Hug-Hellmuth and Melanie Klein. Fleeing the Nazis, she continued her work in London, founding the Hampstead Child Therapy Course and Clinic, later known as the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families in 1952[1†].

Early Years and Education

Anna Freud, born on 3 December 1895 in Vienna, Austria-Hungary, was the sixth and youngest child of Sigmund Freud and Martha Bernays[1†]. Growing up in “comfortable bourgeois circumstances,” Anna displayed a lively imagination, often immersing herself in stories and inventing her own[1†][2†]. However, her childhood was marked by challenges. She struggled to form a close bond with her mother, who was strict and domineering, and felt left out among her five older siblings[1†][2†]. Her relationship with her eldest sister, Sophie, was particularly stormy, characterized by rivalry and jealousy[1†][2†]. Despite these difficulties, Anna found solace in her close relationship with her father, who praised and comforted her during moments of emotional distress[1†][2†].

Anna’s early memories included a family holiday where she was left behind while others went off in a boat. Her father’s support during that time left a lasting impact on her, perhaps foreshadowing her lifelong dedication to deprived children and her commitment to her father’s work[1†][2†]. As she grew older, Anna developed a precocious interest in her father’s psychoanalytic work and was allowed to attend meetings of the newly established Vienna Psychoanalytical Society[1†]. Her fascination with psychology and her father’s influence shaped her educational path.

In 1912, Anna completed her education at the Cottage Lyceum in Vienna[1†][3†]. Two years later, she traveled to England to improve her English. However, her stay was cut short by World War I, and she returned to Vienna, where she began teaching at her alma mater in 1917[1†][3†]. During this time, Anna also underwent psychoanalysis with her father—an unconventional practice even then—and started her own psychoanalytic practice, focusing specifically on children[1†][4†]. These early experiences laid the foundation for her groundbreaking contributions to child psychoanalysis and her enduring commitment to understanding the human psyche[1†][4†].

Career Development and Achievements

Anna Freud’s career unfolded as a remarkable journey within the realm of psychoanalysis, marked by significant milestones and enduring contributions. Despite being the youngest child of Sigmund Freud, she carved her own path, expanding upon her father’s work and shaping the field of child psychoanalysis.

After completing her education at the Cottage Lyceum in Vienna, Anna embarked on a multifaceted career. Her early experiences as an elementary school teacher and her translation work on her father’s writings deepened her interest in child psychology and psychoanalysis[5†]. In 1923, she established her children’s psychoanalytic practice in Vienna, Austria, where she applied her insights to young patients. Her commitment to understanding the complexities of childhood led her to explore the unique dynamics of the developing psyche, challenging the prevailing belief that children could not be psychoanalyzed[5†][3†].

Anna’s influence extended beyond individual therapy sessions. She served as the general secretary of the International Psychoanalytical Association and played a pivotal role in shaping the Vienna Psycho-Analytic Society[5†][6†]. Her close collaboration with her father continued, and she expanded upon his ideas, particularly in the realm of ego psychology. Her groundbreaking work on defense mechanisms—detailed in her book “The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense” (1936)—provided a comprehensive examination of how the ego protects itself from anxiety[5†]. Concepts such as denial, repression, and suppression, elucidated by Anna, have become fundamental in both clinical practice and everyday language.

In the face of political upheaval, Anna’s resilience shone. Fleeing Vienna due to the Nazi regime, she settled in London, England, where she continued her psychoanalytic practice and furthered her impact. In 1952, she founded the Hampstead Child Therapy Course and Clinic, which later evolved into the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families[5†]. Her dedication to deprived children and her commitment to their well-being underscored her legacy.

Anna’s influence extended beyond her own lifetime. Erik Erikson, a prominent figure in psychology, drew inspiration from her work and expanded the field of psychoanalysis and ego psychology. Her emphasis on the ego’s developmental lines and her nuanced understanding of children’s symptoms during various developmental stages left an indelible mark on the discipline[5†][3†].

Anna Freud’s career exemplifies unwavering dedication, intellectual curiosity, and a profound impact on the field of psychology. Her legacy endures through her writings, her clinical practice, and the generations of analysts she inspired.

First Publication of Her Main Works

Anna Freud, the Austrian-British psychoanalyst, made significant contributions to the field of psychoanalysis through her writings. Let us explore her key works:

- “The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence” (1936): In this classic monograph, Anna Freud delved into ego psychology and defense mechanisms. Drawing on her clinical experience, she emphasized the role of the ego in averting painful ideas, impulses, and feelings. Her insights built upon her father’s work, making this a fundamental contribution to psychoanalytic theory[1†].

- “Infants Without Families” (with Dorothy Burlingham) (1944): Co-authored with Dorothy Burlingham, this work explored the impact of early separation from parents on infants. Anna Freud and Burlingham examined the psychological effects of disrupted family bonds, shedding light on the importance of attachment and caregiving during infancy[1†].

- “Normality and Pathology in Childhood” (1965): In this seminal work, Anna Freud assessed childhood development, focusing on normal and pathological aspects. Her insights provided valuable guidance for understanding the complexities of child psychology. She emphasized the need to consider both typical and atypical developmental trajectories[1†][7†][8†].

Anna Freud’s dedication to child psychoanalysis and her collaborative approach enriched the field, leaving a lasting legacy that continues to influence practitioners and researchers worldwide.[1†][4†][7†][8†]

Analysis and Evaluation

Anna Freud, the Austrian-British psychoanalyst, left an indelible mark on the field of psychology. Let us delve into a critical analysis of her work, considering her style, influences, and lasting impact.

Anna Freud’s writing style was characterized by clarity, precision, and a commitment to empirical evidence. Unlike her father, Sigmund Freud, who often delved into theoretical abstractions, Anna focused on practical applications. Her work emphasized the "importance of the ego" in psychological development, particularly in children. She explored defense mechanisms, ego functions, and the interplay between conscious and unconscious processes. Her monograph, “The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence” (1936), remains a cornerstone of ego psychology[1†]. Anna’s approach was pragmatic, grounded in clinical observations, and accessible to both professionals and the public.

Anna Freud’s collaboration with Melanie Klein significantly shaped her views. While Klein emphasized early object relations and the role of fantasy, Anna focused on ego development and adaptive strategies. Their differing perspectives enriched psychoanalytic theory, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of human psychology. Anna also worked closely with Dorothy Burlingham, co-authoring “Infants Without Families” (1944). Together, they explored the impact of parental separation on infants, highlighting attachment dynamics and the need for consistent caregiving[1†].

Anna Freud’s legacy extends beyond her theoretical contributions. As a pioneer in child psychoanalysis, she established the "Hampstead Child Therapy Course and Clinic" in London. This institution, now known as the "Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families", continues to provide therapy, training, and research. Her emphasis on early intervention, understanding children’s emotional worlds, and collaborative approaches influenced generations of clinicians. Anna’s work bridged theory and practice, emphasizing the importance of context and individual differences. Her place in history is secured as a trailblazer who expanded psychoanalysis beyond the consulting room, advocating for children’s well-being and mental health[1†][7†].

In summary, Anna Freud’s pragmatic style, collaborative spirit, and dedication to child psychology have left an enduring legacy. Her impact reverberates through clinical practice, research, and our understanding of human development[1†][4†][7†][8†]

Personal Life

Anna Freud (1895–1982) was the sixth and youngest child of Sigmund Freud and Martha Bernays. Born in Vienna, Austria-Hungary, on December 3, 1895, she grew up in comfortable bourgeois circumstances[1†]. However, her childhood was marked by challenges. Anna never formed a close or pleasurable relationship with her mother, instead finding solace in their Catholic nurse, Josephine. Her relationship with her eldest sister, Sophie, was also strained, leading to a division of territories between them[1†]. Anna’s candid letters to her father revealed emotional struggles, including unreasonable thoughts and feelings. She even faced mild eating disorders and was sent to health farms for rest and rejuvenation[1†].

Despite these difficulties, Anna shared a unique bond with her father. Freud once wrote to his friend Wilhelm Fliess, describing Anna as “downright beautiful through naughtiness” during her lively and mischievous adolescence[1†]. Her precocious interest in her father’s work led her to attend meetings of the newly established Vienna Psychoanalytical Society, where she gained insights into psychoanalysis[1†].

Conclusion and Legacy

Anna Freud (1895–1982) left an indelible mark on the field of psychoanalysis, particularly in the realm of child psychology. Her legacy endures through her pioneering work, insightful contributions, and tireless dedication to understanding the human psyche.

Compared to her father, Sigmund Freud, Anna emphasized the significance of the ego and its “developmental lines.” Her approach incorporated collaborative efforts across various analytical and observational contexts, recognizing the importance of interdisciplinary work[1†]. Her insights into child development and the role of the ego continue to shape contemporary psychoanalytic practice.

In 1938, as the Nazi regime forced the Freud family to flee Vienna, Anna relocated to London. There, she resumed her psychoanalytic practice and established the Hampstead Child Therapy Course and Clinic in 1952. This institution, now known as the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families, remains a hub for therapy, training, and research in child psychoanalysis[1†].

Anna’s commitment to understanding the inner world of children and adolescents has influenced generations of practitioners. Her work transcends national boundaries, reflecting her dual identity as both an Austrian-born individual and a British psychoanalyst. Today, her legacy lives on in the countless lives she touched, the therapeutic approaches she championed, and the ongoing exploration of the human mind[1†].

Key Information

- Also Known As: Anna Freud

- Born: December 3, 1895, in Vienna, Austria-Hungary[1†][7†]

- Died: October 9, 1982, in London, England[1†][7†]

- Nationality: Austrian (1895–1946), British (1946–1982)[1†]

- Occupation: Psychoanalyst[1†]

- Notable Works: Contributions to ego psychology, identification of defense mechanisms[1†]

- Notable Achievements: Founder of child psychoanalysis[1†][7†]

References and Citations:

- Wikipedia (English) - Anna Freud [website] - link

- Freud Museum London - Anna Freud's Early Life [website] - link

- Simply Psychology - Anna Freud: Theory & Contributions To Psychology [website] - link

- ThoughtCo - Anna Freud, Founder of Child Psychoanalysis [website] - link

- Verywell Mind - Anna Freud Biography (1895-1982) [website] - link

- Jewish Women's Archive - Sharing Stories [website] - link

- Britannica - Anna Freud: Austrian-British psychoanalyst [website] - link

- Encyclopedia.com - Freud, Anna (1895–1982) [website] - link

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; additional terms may apply.

Ondertexts® is a registered trademark of Ondertexts Foundation, a non-profit organization.