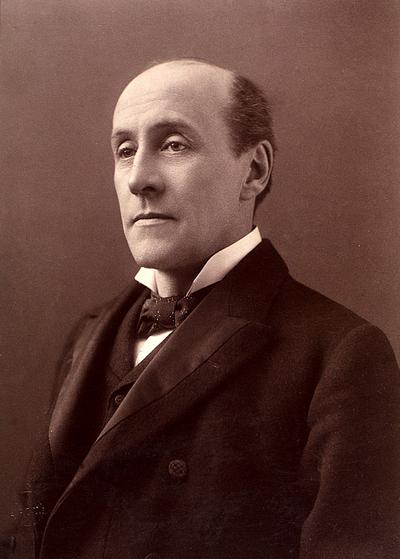

Anthony Hope

Anthony Hope[1†]

Anthony Hope[1†]Sir Anthony Hope Hawkins, better known as Anthony Hope (9 February 1863 – 8 July 1933), was a British novelist and playwright[1†][2†][3†][4†]. He was a prolific writer, especially of adventure novels[1†][2†][3†][4†]. However, he is remembered predominantly for only two books: The Prisoner of Zenda (1894) and its sequel Rupert of Hentzau (1898)[1†][2†][3†][4†].

Early Years and Education

Anthony Hope, born as Anthony Hope Hawkins on 9 February 1863 in Clapton, London, England[1†][2†], embarked on his educational journey at St John’s School, Leatherhead[1†]. He then attended Marlborough College[1†][2†], a renowned independent school in Marlborough, Wiltshire, England, known for its commitment to academic excellence.

Following his time at Marlborough, Hope was accepted into Balliol College, Oxford[1†][2†]. Balliol, one of the oldest and most prestigious colleges at the University of Oxford, is known for producing numerous notable alumni, including several Nobel laureates and former prime ministers.

During his time at Oxford, Hope had an academically distinguished career. He obtained first-class honours in Classical Moderations (Literis Graecis et Latinis) in 1882[1†]. This discipline, also known as “Mods,” involves the intensive study of Latin and Ancient Greek languages and literature, and is considered one of the most rigorous and prestigious courses at Oxford.

Hope continued his academic success by achieving first-class honours in Literae Humaniores (‘Greats’) in 1885[1†]. ‘Greats’ is the final honour school of the classical undergraduate degree at Oxford, encompassing the study of philosophy, ancient history, and classical literature.

After his successful academic career at Oxford, Hope trained as a lawyer and barrister, being called to the Bar by the Middle Temple in 1887[1†][2†][5†]. The Middle Temple is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers.

Career Development and Achievements

Anthony Hope began his career as a lawyer and barrister, being called to the Bar by the Middle Temple in 1887[1†][2†][5†]. He served his pupillage under the future Liberal Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, who thought him a promising barrister and who was disappointed by his decision to turn to writing[1†].

Hope had time to write, as his working day was not overfull during these early years and he lived with his widowed father, then vicar of St Bride’s Church, Fleet Street[1†]. His short pieces appeared in periodicals but for his first book, he was forced to resort to a self-publishing press[1†]. A Man of Mark (1890) is notable primarily for its similarities to Zenda: it is set in an imaginary country, Aureataland, and features political upheaval and humour[1†].

More novels and short stories followed, including Father Stafford in 1891 and the mildly successful Mr Witt’s Widow in 1892[1†]. He stood as the Liberal candidate for Wycombe in the election of 1892 but was not elected[1†].

In 1893, he wrote three novels (Sport Royal, A Change of Air and Half-a-Hero) and a series of sketches that first appeared in The Westminster Gazette and were collected in 1894 as The Dolly Dialogues, illustrated by Arthur Rackham[1†]. Dolly was his first major literary success[1†].

The idea for Hope’s tale of political intrigue, The Prisoner of Zenda, being the history of three months in the life of an English gentleman, came to him at the close of 1893 as he was walking in London[1†]. Hope finished the first draft in a month and the book was in print by April[1†]. The immediate success of The Prisoner of Zenda (1894), his sixth novel—and its sequel, Rupert of Hentzau (1898)—turned him into a celebrated author[1†][2†].

First Publication of His Main Works

Anthony Hope was a prolific writer, and his works have had a significant impact on English literature. Here are some of his main works:

- The Prisoner of Zenda (1894)[1†][6†]: This is perhaps Hope’s most famous work. The novel tells the story of an Englishman who impersonates the king of a fictional country. The book was a huge success and has been adapted into numerous films[1†][6†].

- Rupert of Hentzau (1898)[1†][6†]: This book is a sequel to The Prisoner of Zenda. The story continues with the adventures of the characters from the first book[1†][6†].

- The Dolly Dialogues (1894)[1†][7†]: This is a series of sketches that first appeared in The Westminster Gazette. They were later collected and published as a book[1†][7†].

- The Heart of Princess Osra (1896)[1†][6†]: This book is part of the Ruritania Trilogy, which also includes The Prisoner of Zenda and Rupert of Hentzau[1†][6†].

- The Indiscretion of the Duchess (1897)[1†][6†][7†]: This is another one of Hope’s adventure novels[1†][6†][7†].

- Phroso (1897)[1†][6†]: This novel tells the story of a love affair between an Englishman and a Greek woman[1†][6†].

- The King’s Mirror (1898)[1†][6†]: This is a historical novel set in the 17th century[1†][6†].

- Sophy Of Kravonia (1906)[1†][6†]: This book is a romance novel set in a fictional country[1†][6†].

- The Secret of the Tower (1919)[1†][6†][7†]: This is a mystery novel involving a secret society[1†][6†][7†].

Each of these works showcases Hope’s ability to create engaging narratives and memorable characters. His books have been enjoyed by readers for many generations[1†][6†].

Analysis and Evaluation

Anthony Hope’s works, particularly “The Prisoner of Zenda” and its sequel “Rupert of Hentzau”, are considered “minor classics” of English literature[8†][1†][9†]. They have spawned an entire sub-genre of stories set in fictional Eastern European countries during the nineteenth century, known as Ruritanian romance[8†][1†][9†].

“The Prisoner of Zenda” is a cult classic and a piece of light fiction meant to thrill and entertain casual readers[8†]. The central conceit of the book—that an English gentleman must impersonate the king to preserve the political order—is based on a very old plot device, that of mistaken identity[8†]. The story is very formulaic, which is in keeping with its light tone[8†].

Another aspect of the novel is its view of the English gentleman and the sense of natural superiority the ruling class assumes[8†]. The book is a celebration of the chivalrous values of honor, truthfulness, courage, modesty, and kindness toward women[8†]. These set values call on tropes found as far back as Arthurian literature, which conjures ideas of chivalrous men, courtly love, and delineated virtue[8†].

Hope’s works are a comforting if misguided look into the past, one which takes root in the nineteenth and twentieth-century British values[8†]. His novels are a nostalgic look at the romanticized, “less-civilized” world of Eastern Europe that, to the British eye, must be filled with fantastic kingdoms filled with drama, beautiful women, dashing heroes, and dastardly villains[8†].

Personal Life

Anthony Hope married Elizabeth Somerville in 1903[1†][10†][5†]. The couple had two sons and a daughter[1†][10†][5†]. In 1918, Hope was knighted for his contribution to propaganda efforts during World War I[1†]. After being knighted, he bought a country estate at Tadworth in Surrey, where he spent the rest of his life[1†][10†][5†]. He continued to write more books and several plays[1†][10†][5†]. He passed away in 1933 at the age of 70[1†][10†][5†].

Conclusion and Legacy

Anthony Hope’s legacy is primarily tied to his creation of the Ruritanian romance genre with his novels “The Prisoner of Zenda” and "Rupert of Hentzau"[1†]. These works are considered “minor classics” of English literature[1†]. The fictional country of Ruritania, featured in these novels, has inspired many other books set in similar fictional European locales[1†].

His works have had a significant impact on popular culture, inspiring numerous adaptations, including the notable 1937 and 1952 Hollywood movies based on "The Prisoner of Zenda"[1†]. His influence extends beyond literature into the realm of cinema and storytelling, demonstrating the enduring appeal of his imaginative settings and intricate plots[1†].

Hope’s contribution to literature was recognized during his lifetime, and he was knighted in 1918 for his contribution to propaganda efforts during World War I[1†]. His works continue to be read and appreciated for their adventure, romance, and political intrigue[1†].

Key Information

- Also Known As: Sir Anthony Hope Hawkins[1†]

- Born: 9 February 1863, Clapton, London, England[1†]

- Died: 8 July 1933, Walton-on-the-Hill, Surrey, England[1†]

- Nationality: British[1†]

- Occupation: Barrister, Writer[1†]

- Notable Works: The Prisoner of Zenda (1894), Rupert of Hentzau (1898)[1†]

- Notable Achievements: His works, especially The Prisoner of Zenda and its sequel Rupert of Hentzau, are considered “minor classics” of English literature and have inspired many adaptations[1†].

References and Citations:

- Wikipedia (English) - Anthony Hope [website] - link

- Britannica - Anthony Hope: English author [website] - link

- Pantheon - Anthony Hope Biography - English novelist (1863-1933) [website] - link

- HowOld.co - Anthony Hope Biography [website] - link

- IMDb - Anthony Hope - Biography [website] - link

- Goodreads - Author: Books by Anthony Hope (Author of The Prisoner of Zenda) [website] - link

- The Project Gutenberg - INDEX OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG [website] - link

- eNotes - The Prisoner of Zenda Analysis [website] - link

- Goodreads - Book: The Complete Works of Anthony Hope [website] - link

- IMDb - Anthony Hope [website] - link

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; additional terms may apply.

Ondertexts® is a registered trademark of Ondertexts Foundation, a non-profit organization.