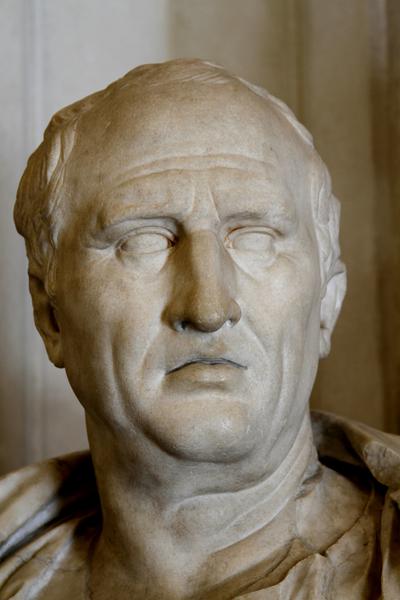

Marcus Tullius Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero[2†]

Marcus Tullius Cicero[2†]Marcus Tullius Cicero, also known as Cicero, was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, and writer who tried to uphold republican principles during the final civil wars that destroyed the Roman Republic[1†][2†]. He was born on January 3, 106 BC, in Arpinum, Latium (now Arpino, Italy) and died on December 7, 43 BC, in Formiae, Latium (now Formia)[1†][2†].

Early Years and Education

Marcus Tullius Cicero was born in the hill town of Arpinum, about 60 miles southeast of Rome[3†]. His father, a wealthy member of the equestrian order, paid to educate Cicero and his younger brother in philosophy and rhetoric in Rome and Greece[3†]. This education laid the foundation for Cicero’s future achievements in law, politics, and literature.

At the age of 17, Cicero served in the Social War under Pompeius Strabo (the father of the statesman and general Pompey)[3†][4†]. This period of political upheaval in Rome, the 80s BCE, marked the end of Cicero’s formal education[3†][4†].

Cicero’s first appearance in the courts was in 81 BC, where he successfully defended Publius Quinctius against a fabricated charge of parricide[3†][1†]. This brilliant defense established his reputation at the bar[3†][1†]. He started his public career as quaestor (an office of financial administration) in western Sicily in 75 BC[1†].

Career Development and Achievements

After serving in the military, Cicero studied Roman law[5†]. He quickly became famous for taking risky cases and winning them[5†][6†]. His brilliant defense of Sextus Roscius against a fabricated charge of parricide established his reputation at the bar[5†][1†]. He started his public career as quaestor (an office of financial administration) in western Sicily in 75 BC[5†][1†].

Cicero was elected to each of Rome’s principal offices, becoming the youngest citizen to attain the highest rank of consul without coming from a political family[5†]. He was a strong believer in the Roman Republic and wanted to climb the ladder of political office in the traditional manner called the Cursus honorum[5†][6†].

In 63 BC, Cicero gave an impassioned oration to his fellow senators that charged Catiline with plotting to stage a violent coup[5†][7†]. This so moved the Senate that they voted to implement martial law and execute the conspirators[5†][7†]. Cicero was named pater patriae —“father of the country”—for his service to the republic[5†][7†].

Cicero was an accomplished orator and successful lawyer but is best known for his philosophical writings[5†][8†]. He also believed that his political career was his most important achievement[5†][8†]. While serving in the government, there was an attempt to overthrow the government[8†].

First Publication of His Main Works

Cicero’s writings constitute one of the most renowned collections of historical and philosophical work in all of classical antiquity[9†]. His works include books of rhetoric, orations, philosophical and political treatises, and letters[9†][1†]. He introduced the Romans to the chief schools of Greek philosophy and created a Latin philosophical vocabulary[9†].

Here are some of his notable works:

- Orations: Cicero’s orations, such as “In Verrem” and “In Catilinam I–IV”, are some of his most famous works[9†]. These speeches showcase his skill as an orator and his commitment to upholding Roman law and order[9†].

- Philosophical Works: Cicero’s philosophical works, including “De Oratore”, “De Re Publica”, “De Legibus”, “De Finibus”, and “De Natura Deorum”, introduced Greek philosophy to the Romans[9†]. His work “De Officiis” is a treatise on ethics that was highly influential in the Middle Ages[9†].

- Letters: Cicero’s letters offer a unique insight into the political and social life of the late Roman Republic[9†]. His letters to his friend Atticus are especially influential, introducing the art of refined letter writing to European culture[9†].

Cicero’s works were enormously influential in later periods[9†][10†]. His writings not only provide a reflection of his own time but also offer timeless insights into human nature and society[9†].

Analysis and Evaluation

Cicero’s influence on Latin literature and rhetoric is profound[11†]. His works, which include orations, philosophical treatises, and letters, have been studied and analyzed for their literary style and rhetorical strategies[11†].

Cicero’s orations, such as “In Verrem” and “In Catilinam I–IV”, are renowned for their eloquence and effectiveness[11†]. His courtroom techniques, such as “passing over” a subject to emphasize it, have been noted for their ingenuity[11†]. Cicero’s defense of rhetoric, despite its negative connotations, demonstrates his belief in the power of persuasive speech[11†].

His philosophical works introduced Greek philosophy to the Romans and created a Latin philosophical vocabulary[11†]. Cicero’s treatises, such as “De Oratore”, “De Re Publica”, “De Legibus”, “De Finibus”, and “De Natura Deorum”, have been critically evaluated for their insights into various philosophical schools[11†]. His work “De Officiis”, a treatise on ethics, was highly influential in the Middle Ages[11†].

Cicero’s letters offer a unique insight into the political and social life of the late Roman Republic[11†]. His letters to his friend Atticus are especially influential, introducing the art of refined letter writing to European culture[11†].

Cicero’s works have been analyzed for their content and intention, providing a better understanding of the trial of Caelius and Cicero’s speech[11†][12†]. His writings not only provide a reflection of his own time but also offer timeless insights into human nature and society[11†].

Despite the challenges he faced in his career, Cicero’s writings have barely waned in influence over the centuries[11†]. His works continue to be studied and admired for their literary style, rhetorical strategies, and philosophical insights[11†].

Personal Life

Marcus Tullius Cicero’s personal life was deeply intertwined with his career as a significant politician of the Roman Republic[13†]. He married Terentia in 79 BC, a union that was more of convenience than love, and it brought him considerable wealth[13†][14†]. Despite the practical nature of his marriage, Cicero deeply loved his children from the union, Tullia and Marcus[13†][14†].

His relationship with Terentia became noticeably strained during the time of the civil wars, as shown in Cicero’s correspondence with his wife[13†][14†]. His sensitive and impressionable personality often led him to overreact in the face of political and private change[13†]. C. Asinius Pollio, a contemporary Roman statesman and historian, once remarked, "Would that he had been able to endure prosperity with greater self-control and adversity with more fortitude!"[13†]

Cicero’s personal life provided the underpinnings of one of the most significant politicians of the Roman Republic[13†]. His personal life, relationships, family, and other notable aspects outside his professional career were all factors that shaped his legacy[13†].

Conclusion and Legacy

Marcus Tullius Cicero’s legacy is profound and enduring, influencing generations long after his death[3†][1†]. His inventive command of Latin prose provided a model for generations of textbooks and grammars[3†]. The Church Fathers explored Greek philosophy through Cicero’s translations, and many historians date the start of the Renaissance to Petrarch’s rediscovery of Cicero’s letters in 1345[3†].

Cicero’s thought reflected his holistic view of morality, political order, and the wisdom of effective speech[3†][15†]. He is remembered for his strong defense of the values of the Roman Republic and rejection of the tyranny he believed Julius Caesar, and then Mark Antony, embodied[3†][16†].

Greek philosophy and rhetoric moved fully into Latin for the first time in the speeches, letters, and dialogues of Cicero[3†]. His writings barely waned in influence over the centuries. It was through him that the thinkers of the Renaissance and Enlightenment discovered the riches of Classical rhetoric and philosophy[3†].

Cicero’s legacy is not just limited to his contributions to philosophy and rhetoric. His political career, marked by his staunch defense of the Roman Republic’s values, has also left a lasting impact[3†][16†]. Despite the political turmoil of his time, Cicero’s writings and speeches provide a valuable insight into the political and social climate of the late Roman Republic[3†][1†].

Key Information

- Also Known As: Tully[1†]

- Born: 106 BC, Arpinum, Latium (now Arpino, Italy)[1†]

- Died: December 7, 43 BC, Formiae, Latium (now Formia)[1†]

- Nationality: Roman[1†]

- Occupation: Statesman, lawyer, scholar, and writer[1†]

- Notable Works: Cicero’s notable works include “Academic Philosophy”, “Ad Atticum”, “Ad Brutum”, “Ad Quintum fratrem”, “Ad familiares”, “Brutus”, “De consolatione”, “De finibus”, “De legibus”, “De oratore”, “For Milo”, “On Duties”, “On His Consulship”, “On His Life and Times”, “On the Nature of the Gods”, “On the Republic”, “Pro Cluentio”, “Pro Murena”, “Pro Sulla”, “Tusculanae disputationes” and many more[1†].

- Notable Achievements: Cicero was the first of his family to achieve Roman office[1†][3†]. He was one of the leading political figures of the era of Julius Caesar, Pompey, Marc Antony, and Octavian[1†][3†]. He was elected consul in 63 BC[1†][17†]. He is remembered in modern times as the greatest Roman orator and the innovator of what became known as Ciceronian rhetoric[1†].

References and Citations:

- Britannica - Cicero: Roman statesman, scholar, and writer [website] - link

- Wikipedia (English) - Cicero [website] - link

- History - Marcus Tullius Cicero - Biography, Letters & Legacy [website] - link

- World History - Cicero [website] - link

- National Geographic Education - Cicero [website] - link

- Sage-Advices - What was the greatest achievement of Cicero? [website] - link

- Britannica - What was Marcus Tullius Cicero’s greatest achievement? [website] - link

- Discover Walks Blog - Top 10 Remarkable Facts about Cicero [website] - link

- Wikipedia (English) - Writings of Cicero [website] - link

- Oxford Bibliographies - Cicero - Classics [website] - link

- eNotes - Cicero Analysis [website] - link

- JSTOR - Cicero's Analysis of the Prosecution Speeches in the Pro Caelio: An Exercise in Practical Criticism [website] - link

- Wikipedia (English) - Personal life of Cicero [website] - link

- SunSigns - Cicero Biography, Life, Interesting Facts [website] - link

- Feelosofi - Cicero [website] - link

- National Geographic - How Cicero's murder ushered in the Roman Empire [website] - link

- Britannica - Marcus Tullius Cicero summary [website] - link

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; additional terms may apply.

Ondertexts® is a registered trademark of Ondertexts Foundation, a non-profit organization.