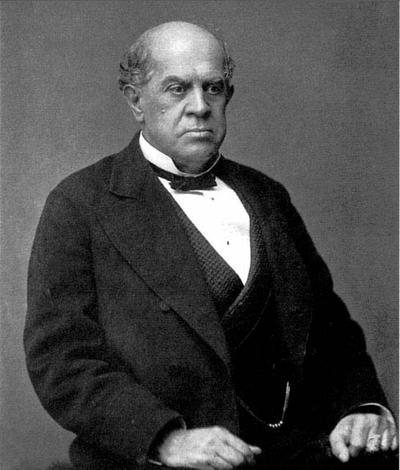

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento[1†]

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento[1†]Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (born February 14, 1811, San Juan, Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata now in Argentina[[?]]—died September 11, 1888, Asunción, Paraguay) was an Argentine activist, intellectual, writer, statesman and the seventh President of Argentina[1†]. His writing spanned a wide range of genres and topics, from journalism to autobiography, to political philosophy and history[1†]. He was a member of a group of intellectuals, known as the Generation of 1837, who had a great influence on 19th-century Argentina[1†]. He was particularly concerned with educational issues and was also an important influence on the region’s literature[1†].

Early Years and Education

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento was born on February 15, 1811, in San Juan, an old and primitive town of western Argentina near the Andes[2†]. His parents were humble and hardworking, living in near poverty[2†]. Despite these challenging circumstances, Sarmiento was largely self-taught, reading whatever came within his reach[2†]. His formal education was scanty[2†].

An early intellectual influence was a maternal uncle and private tutor, the priest José de Oro[2†][3†]. Steeped in the classics, the Bible, Latin, and French, Sarmiento began teaching elementary school in his teens[2†][3†]. Post-Independence chaos and anarchy awakened his interest in orderly government[2†][3†]. By 1829 he fought with the unitarists against caudillo rule[2†][3†].

At the age of 15, Sarmiento began his career as a rural schoolteacher[2†][4†]. He soon entered public life as a provincial legislator[2†][4†]. His political activities and his outspokenness provoked the rage of the military dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas, who exiled him to Chile in 1840[2†][4†]. There, Sarmiento was active in politics and became an important figure in journalism through his articles in the Valparaíso newspaper El Mercurio[4†]. In 1842, he was appointed founding director of the first teachers’ college in South America and began to give effect to a lifelong conviction that the primary means to national development was through a system of public education[2†][4†].

Career Development and Achievements

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento’s career was marked by his rise from a rural schoolmaster to the president of Argentina[4†][1†]. His political activities and outspokenness provoked the rage of the military dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas, who exiled him to Chile in 1840[4†][1†]. In Chile, Sarmiento became an important figure in journalism through his articles in the Valparaíso newspaper El Mercurio[4†][1†]. He was also active in politics during his time in Chile[4†][1†].

In 1842, Sarmiento was appointed the founding director of the first teachers’ college in South America[4†][1†]. This appointment marked the beginning of his lifelong conviction that the primary means to national development was through a system of public education[4†][1†]. During his time in Chile, Sarmiento wrote Facundo, an impassioned denunciation of Rosas’s dictatorship in the form of a biography of Juan Facundo Quiroga, Rosas’s tyrannical gaucho lieutenant[4†][1†]. The book brought him far more than just literary recognition; he expended his efforts and energy on the war against dictatorships, specifically that of Rosas[4†][1†].

Sarmiento served as the president of Argentina from 1868 to 1874[4†][1†]. As president, he laid the foundation for later national progress by fostering public education, stimulating the growth of commerce and agriculture, and encouraging the development of rapid transportation and communication[4†][1†]. He also took advantage of the opportunity to modernize and develop train systems, a postal system, and a comprehensive education system[4†][1†]. He spent many years in ministerial roles on the federal and state levels where he traveled abroad and examined other education systems[4†][1†].

First Publication of His Main Works

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento was a prolific writer, and his works have had a significant impact on both Argentine and Latin American literature. Here are some of his main works:

- Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism[4†][1†]: This is arguably Sarmiento’s most famous work. Written during his exile in Chile, it is a critique of the dictatorship of Juan Manuel de Rosas. The book contrasts enlightened Europe, where democracy, social services, and intelligent thought were valued, with the barbarism of the gaucho and especially the caudillo, the ruthless strongmen of nineteenth-century Argentina[4†][1†]. It is not only a literary achievement but also a political statement against dictatorships[4†][1†].

- Recuerdos de Provincia[4†][5†][6†]: This book is a collection of Sarmiento’s memories of his province. It provides a unique insight into his personal experiences and the socio-political context of his time[4†][5†][6†].

- Viajes por Europa, África i América[4†][5†]: Published in two volumes in 1849 and 1851, this work is a collection of Sarmiento’s travel writings. It reflects his observations and experiences during his travels across Europe, Africa, and America[4†][5†].

These works were not only significant in their content but also in their style. Sarmiento’s writing, which spanned a wide range of genres and topics, from journalism to autobiography, to political philosophy and history, had a great influence on 19th-century Argentina[4†][1†].

Analysis and Evaluation

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento’s work has been the subject of extensive analysis and evaluation. His writings, particularly his critique of Juan Manuel de Rosas in “Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism”, have been recognized for their significant impact on both Argentine and Latin American literature[4†][7†].

Sarmiento’s work is characterized by its ambitious attempt to reshape Argentina into a modern, export economy society[4†][6†]. His writings are seen as an integral part of his political project, with his literary and political ambitions being inextricably linked[4†][6†]. His focus on education as a primary means to national development was a reflection of his belief in the power of knowledge and learning[4†].

However, his works have also been criticized for their erratic style and oversimplifications[4†][8†]. Despite these criticisms, Sarmiento’s influence on Argentine and Latin American literature is undeniable[4†][7†]. His depiction of the gaucho and the pampas in “Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism” has made the book a classic of Latin American literature[4†].

Sarmiento’s legacy is complex and multifaceted. As a writer, he is remembered for his contributions to literature and his unique style. As a statesman, he is recognized for his efforts to modernize Argentina and promote education[4†]. His work continues to be studied and analyzed, contributing to our understanding of 19th-century Argentina and Latin America[4†][7†].

Personal Life

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento was born on February 15, 1811, in San Juan, an old and primitive town of western Argentina near the Andes[2†]. His parents were humble and hardworking, living in near poverty[2†]. His formal education was scanty, and he was largely self-taught, reading whatever came within his reach[2†].

Sarmiento was married to Benita Martínez Pastoriza in 1847, but they separated in 1857[2†][1†]. After his separation, he had a domestic partnership with Aurelia Vélez Sársfield that lasted from 1857 until his death in 1888[2†][1†]. He had two children, Ana Faustina and Domingo Fidel[2†][1†].

Throughout his life, Sarmiento continued to write extensively[2†][9†]. He was honored in 1943 by the creation of the Panamerican Teachers’ Day[2†][9†]. A statue of him stands in Boston; another by Rodin is in Buenos Aires[2†][9†].

Sarmiento died in 1888 of a heart attack[2†][9†]. He was 77 years old[2†][9†].

Conclusion and Legacy

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, an Argentine activist, intellectual, writer, statesman, and the seventh President of Argentina, left a profound legacy in his country and Latin America[4†][1†]. His work spanned a wide range of genres and topics, from journalism to autobiography, to political philosophy and history[4†][1†]. He was a member of a group of intellectuals, known as the Generation of 1837, who had a significant influence on 19th-century Argentina[4†][1†].

Sarmiento’s greatest literary achievement was Facundo, a critique of Juan Manuel de Rosas, that Sarmiento wrote while working for the newspaper El Progreso during his exile in Chile[4†][1†]. The book brought him far more than just literary recognition; he expended his efforts and energy on the war against dictatorships, specifically that of Rosas, and contrasted enlightened Europe—a world where, in his eyes, democracy, social services, and intelligent thought were valued—with the barbarism of the gaucho and especially the caudillo, the ruthless strongmen of nineteenth-century Argentina[4†][1†].

While president of Argentina from 1868 to 1874, Sarmiento championed intelligent thought—including education for children and women—and democracy for Latin America[4†][1†]. He also took advantage of the opportunity to modernize and develop train systems, a postal system, and a comprehensive education system[4†][1†]. He spent many years in ministerial roles on the federal and state levels where he traveled abroad and examined other education systems[4†][1†].

Sarmiento is now sometimes considered “The Teacher” of Latin America[4†][10†]. He saw himself as the standard-bearer of European liberalism in Spanish America and the architect of a nation built on its ideals[6†]. His loving depiction of the gaucho and the pampas has made Facundo a classic of Latin American literature[4†].

Key Information

- Also Known As: Domingo Faustino Fidel Valentín Sarmiento y Albarracín[1†]

- Born: February 14, 1811, San Juan, Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata (now in Argentina)[1†][4†][1†]

- Died: September 11, 1888, Asunción, Paraguay (aged 77)[1†][4†][1†]

- Nationality: Argentine[1†]

- Occupation: Educator, statesman, writer, and President of Argentina[1†][4†][1†]

- Notable Works: "Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism"[1†][4†][1†]

- Notable Achievements: Sarmiento rose from a position as a rural schoolmaster to become president of Argentina (1868–74). As president, he laid the foundation for later national progress by fostering public education, stimulating the growth of commerce and agriculture, and encouraging the development of rapid transportation and communication[1†][4†][1†].

References and Citations:

- Wikipedia (English) - Domingo Faustino Sarmiento [website] - link

- Encyclopedia.com - Domingo Faustino Sarmiento [website] - link

- Encyclopedia.com - Sarmiento, Domingo Faustino (1811–1888) [website] - link

- Britannica - Domingo Faustino Sarmiento: president of Argentina [website] - link

- eNotes - Domingo Faustino Sarmiento Critical Essays [website] - link

- De Gruyter - Sarmiento [website] - link

- Springer Link - Argentinean Literary Orientalism - Chapter: An Ideological Reading of Domingo Faustino Sarmiento [website] - link

- Duke University Press - Hispanic American Historical Review - Domingo Faustino Sarmiento [website] - link

- GradeSaver - Domingo F. Sarmiento Biography [website] - link

- Goodreads - Author: Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (Author of Facundo) [website] - link

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; additional terms may apply.

Ondertexts® is a registered trademark of Ondertexts Foundation, a non-profit organization.