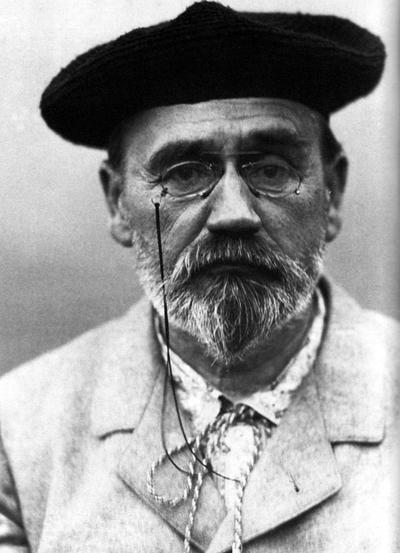

Émile Zola

Émile Zola[1†]

Émile Zola[1†]Émile Zola, born Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola on April 2, 1840, in Paris, was a prominent French novelist, journalist, and playwright, renowned for his pioneering role in the literary school of naturalism. He significantly contributed to the political liberalization of France and played a crucial role in the exoneration of Alfred Dreyfus through his famous open letter "I Accuse...!" (J’Accuse…!). Zola’s literary achievements include the monumental 20-novel series "The Rougon-Macquart" (Les Rougon-Macquart) and his nominations for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1901 and 1902[1†][2†].

Early Years and Education

Émile Zola was born on April 2, 1840, in Paris, to François Zola, an Italian engineer of Greek descent, and Émilie Aubert, a Frenchwoman[1†][2†]. His father, originally named Francesco Zolla, was instrumental in engineering the Zola Dam in Aix-en-Provence, where the family moved when Émile was three years old[1†][2†]. The early death of his father in 1847 left the family in financial hardship, profoundly impacting Zola’s childhood[1†][2†].

Zola’s early education took place at the Collège Bourbon in Aix-en-Provence, where he formed a lifelong friendship with the future painter Paul Cézanne[1†][2†]. Despite the challenges of poor nutrition and bullying at school, Zola’s intellectual curiosity flourished[1†][2†]. In 1858, the family relocated to Paris, and Zola continued his education at the Lycée Saint-Louis[1†][2†]. However, he struggled academically, failing the baccalauréat examination twice, which thwarted his mother’s hopes for him to pursue a law career[1†][2†].

During his adolescence, Zola’s passion for literature began to take shape. He started writing in the Romantic style, influenced by his readings and the cultural milieu of Paris[1†][2†]. To support himself, he took on various low-paying jobs, including working as a clerk in a shipping firm and later in the sales department of the publisher Hachette[1†][2†]. These experiences, coupled with his early literary endeavors, laid the foundation for his future career as a writer[1†][2†].

Career Development and Achievements

Émile Zola’s career began in earnest when he joined the publishing firm Hachette in 1862, initially working as a clerk before moving to the advertising department[2†][3†]. His first novel, "Claude's Confession" (La Confession de Claude), published in 1865, garnered attention for its autobiographical elements and controversial themes[2†][3†]. This early success allowed Zola to leave Hachette and pursue writing full-time[2†][3†].

Zola’s breakthrough came with the publication of "Thérèse Raquin" in 1867, a novel that established his reputation as a leading naturalist writer[2†][3†]. The novel’s stark portrayal of human passion and its consequences set the tone for his future works[2†][3†]. In 1871, Zola began his ambitious 20-novel series "The Rougon-Macquart" (Les Rougon-Macquart), which aimed to depict the impact of heredity and environment on a family during the Second French Empire[2†][3†]. The series includes notable works such as "The Drinking Den" (L’Assommoir, 1877), which explores the destructive effects of alcoholism, and "Germinal" (1885), a powerful depiction of a coal miners’ strike[2†][3†].

Zola’s commitment to naturalism extended beyond his novels. He articulated his literary philosophy in "The Experimental Novel" (Le Roman expérimental, 1880), where he argued that the novelist should adopt the methods of a scientist, observing and documenting human behavior with detachment[2†][3†]. This approach influenced his contemporaries and solidified his position as a central figure in the naturalist movement[2†][3†].

In addition to his literary achievements, Zola played a significant role in the political sphere. His involvement in the Dreyfus Affair, a political scandal that divided France, was particularly notable[2†][3†]. In 1898, Zola published "I Accuse...!" (J’Accuse…!), an open letter to the President of France, accusing the government and military of anti-Semitism and wrongful imprisonment of Alfred Dreyfus[2†][3†]. This bold act of advocacy not only contributed to Dreyfus’s eventual exoneration but also underscored Zola’s commitment to justice and truth[2†][3†].

Throughout his career, Zola continued to produce influential works. His later novels, such as "Lourdes" (1894), "Rome" (1896), and "Paris" (1898), reflect his interest in social and religious issues[2†][3†]. Despite facing legal challenges and public backlash, Zola remained steadfast in his literary and political pursuits[2†][3†]. His dedication to his craft and his principles earned him nominations for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1901 and 1902[2†][3†].

Zola’s legacy is marked by his profound impact on literature and society. His naturalist approach paved the way for modern social novels, and his fearless advocacy for justice left an indelible mark on French history[2†][3†]. His works continue to be studied and celebrated for their unflinching portrayal of human nature and social realities[2†][3†].

First publication of his main works

- Le Paradis des chats (Le Paradis des chats, 1864): A whimsical tale that delves into the lives of cats, blending humor and social commentary while celebrating their independence and charm[1†][2†][4†].

- The Fortune of the Rougons (La Fortune des Rougon, 1871): This novel marks the beginning of Zola’s monumental 20-novel series "The Rougon-Macquart" (Les Rougon-Macquart), which explores the lives of two branches of a family during the Second French Empire[1†][2†][4†].

- The Kill / The Rush for the Spoil (La Curée, 1871–72): The second novel in the "The Rougon-Macquart" (Les Rougon-Macquart) series, it delves into the corrupt and decadent lives of Parisian society during the Second Empire[1†][2†][4†].

- The Belly of Paris / The Fat and the Thin (Le Ventre de Paris, 1873): This novel, the third in the series, portrays the bustling life of the Parisian markets and the struggles of the working class[1†][2†][4†].

- The Conquest of Plassans (La Conquête de Plassans, 1874): The fourth novel in the series, it examines the political machinations and personal ambitions in a small provincial town[1†][2†][4†].

- The Sin of Abbé Mouret (La Faute de l’Abbé Mouret, 1875): The fifth novel in the series, it tells the story of a young priest’s struggle with his faith and forbidden love[1†][2†][4†].

- His Excellency Eugène Rougon (Son Excellence Eugène Rougon, 1876): The sixth novel in the series, it focuses on the political career of Eugène Rougon and the corrupt world of Second Empire politics[1†][2†][4†].

- The Drinking Den (L’Assommoir, 1877): The seventh novel in the series, it is a powerful depiction of alcoholism and its devastating effects on the working class[1†][2†][4†].

- A Love Story (Une page d’amour, 1878): The eighth novel in the series, it explores the themes of love and loss in the life of a widow and her daughter[1†][2†][4†].

- Nana (1880): The ninth novel in the series, it tells the story of a courtesan’s rise and fall in Parisian society[1†][2†][4†].

- Pot Luck / Piping Hot! (Pot-Bouille, 1882): The tenth novel in the series, it offers a satirical look at the bourgeoisie and their hypocritical morals[1†][2†][4†].

- For a Night of Love (Pour une nuit d'amour, 1883):A passionate narrative that examines the complexities of love and desire, set against the backdrop of Parisian nightlife and romantic encounters[1†][2†][4†].

- The Ladies Paradise / The Ladies' Delight (Au Bonheur des Dames, 1883): The eleventh novel in the series, it depicts the rise of a department store and its impact on small businesses and the lives of its employees[1†][2†][4†].

- The Bright Side of Life (La joie de vivre, 1884): The twelfth novel in the series, it explores the themes of optimism and resilience in the face of adversity[1†][2†][4†].

- Germinal (1885): The thirteenth novel in the series, it is a powerful portrayal of a coal miners’ strike and the harsh realities of industrial life[1†][2†][4†].

- The Masterpiece / His Masterpiece (L’Œuvre, 1886): The fourteenth novel in the series, it examines the struggles of an artist and the sacrifices made for art[1†][2†][4†].

- The Earth (La Terre, 1887): The fifteenth novel in the series, it depicts the brutal and often violent life of French peasants[1†][2†][4†].

- The Dream (Le Rêve, 1888): The sixteenth novel in the series, it tells the story of a young girl’s dreams and the harsh realities she faces[1†][2†][4†].

- The Beast Within (La Bête humaine, 1890): The seventeenth novel in the series, it is a psychological thriller that delves into the darker aspects of human nature[1†][2†][4†].

- Money (L’Argent, 1891): The eighteenth novel in the series, it explores the world of finance and the corrupting influence of money[1†][2†][4†].

- The Debacle (La Débâcle, 1892): The nineteenth novel in the series, it provides a harrowing account of the Franco-Prussian War and its aftermath[1†][2†][4†].

- Modern Marriage (Comment on se marie, 1893): A critical examination of the institution of marriage, exploring its social implications and the evolving roles of men and women within it[1†][2†][4†].

- Doctor Pascal (Le Docteur Pascal, 1893): The final novel in the series, it ties together the fates of the Rougon-Macquart family and reflects on the themes of heredity and destiny[1†][2†][4†].

- The Mysteries of Marseilles (Les Mystères de Marseille, 1867): A narrative intertwining various stories set in the port city, reflecting the social fabric and tensions of the time[1†][2†][4†].

- The Fête at Coqueville (La Fête à Coqueville, 1907): A lively depiction of a village festival, exploring the dynamics of community and tradition[1†][2†][4†].

- Madeleine Férat (Madeleine Férat, 1868): A poignant tale of love and tragedy, focusing on the emotional turmoil of a young woman caught between societal expectations and her desires[1†][2†][4†].

- Thérèse Raquin (Thérèse Raquin, 1867): A groundbreaking work that delves into themes of passion, guilt, and the darker side of human nature through the story of an adulterous couple[1†][2†][4†].

- The Flood (L'Inondation, 1880): A short story that vividly portrays the chaos and destruction wrought by a natural disaster, highlighting human resilience[1†][2†][4†].

- Claude's Confession (La Confession de Claude, 1865): A deep exploration of the inner life of an artist, grappling with guilt and artistic ambition[1†][2†][4†].

- Nouveaux Contes à Ninon (1874): A collection of short stories that reflect Zola's keen observations of everyday life and social dynamics[1†][2†][4†].

- The Experimental Novel (Le Roman Expérimental, 1880): A manifesto on Zola’s literary theories, advocating for a scientific approach to writing and the depiction of reality[1†][2†][4†].

- Jacques Damour et autres nouvelles (1880): A collection of short stories exploring themes of love, fate, and the human condition[1†][2†][4†].

-

The Miller's Daughter (L'Attaque du moulin, 1877): A narrative centered on a young woman's romantic entanglements amidst the backdrop of rural life[1†][2†][4†].

-

Death (Comment on meurt, 1883): An exploration of the inevitability of death and the various attitudes toward mortality, reflecting on the emotional and societal implications of loss[1†][2†][4†].

-

Lourdes (1894): A reflective account of faith, healing, and the clash between belief and skepticism at the famous pilgrimage site[1†][2†][4†].

- Rome (1896): A novel that examines the complexities of life in the Eternal City, blending personal and political narratives[1†][2†][4†].

- Paris (1898): A vivid portrayal of Parisian life and its social fabric, capturing the essence of the city’s culture and politics[1†][2†][4†].

- I Accuse...! (J'accuse, 1898): A powerful open letter denouncing the injustices of the Dreyfus Affair, advocating for truth and justice in the face of corruption and anti-Semitism[1†][2†][4†].

- Fruitfulness (Fécondité, 1899): A meditation on family, motherhood, and the role of women in society, highlighting the importance of continuity and growth[1†][2†][4†].

- Work (Travail, 1901): A novel that examines the struggles and aspirations of the working class in the context of the industrial age[1†][2†][4†].

- Truth (Vérité, 1903): An unfinished work that reflects Zola's quest for authenticity and moral clarity in literature and society[1†][2†][4†].

- Justice (Justice, Unfinished): An incomplete exploration of the themes of morality and social justice, delving into the complexities of human behavior[1†][2†][4†].

Analysis and Evaluation

Émile Zola’s literary style is characterized by his meticulous attention to detail and his commitment to the principles of naturalism, a movement he helped to pioneer[1†][2†][4†]. His works often depict the harsh realities of life, focusing on the influence of environment and heredity on human behavior[1†][2†][4†]. Zola’s narrative technique is marked by a scientific approach, where he meticulously documents the lives of his characters, akin to a social experiment[1†][2†][4†]. This method is evident in his 20-novel series "The Rougon-Macquart" (Les Rougon-Macquart), which explores the impact of the Second French Empire on a single family over several generations[1†][2†][4†].

Zola was heavily influenced by the scientific theories of his time, particularly those of Charles Darwin and Claude Bernard[1†][2†][4†]. His novel "Germinal", for instance, is a vivid portrayal of the struggles of coal miners and is considered one of his masterpieces[1†][2†][4†]. The novel’s detailed depiction of the miners’ plight and the oppressive conditions they endure highlights Zola’s commitment to social realism and his ability to evoke empathy in his readers[1†][2†][4†]. Similarly, "Nana" offers a scathing critique of the decadence and moral decay of the bourgeoisie, showcasing Zola’s skill in character development and social commentary[1†][2†][4†].

Zola’s influence extends beyond literature; his involvement in the Dreyfus Affair, particularly through his open letter "I Accuse...!" (J’Accuse…!), underscores his role as a public intellectual and advocate for justice[1†][2†][4†]. This letter, published in 1898, accused the French government of anti-Semitism and wrongful imprisonment of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish army officer[1†][2†][4†]. Zola’s courageous stand in this affair not only highlighted his commitment to truth and justice but also cemented his legacy as a defender of human rights[1†][2†][4†].

Zola’s legacy in literature is profound; he is often regarded as the father of naturalism, and his works have influenced countless writers and thinkers[1†][2†][4†]. His novels continue to be studied for their innovative narrative techniques and their unflinching portrayal of social issues[1†][2†][4†]. Zola’s ability to blend scientific rigor with literary creativity has earned him a lasting place in the canon of world literature[1†][2†][4†]. His works not only provide a window into the social and political issues of his time but also offer timeless insights into the human condition[1†][2†][4†].

Personal Life

Émile Zola was born on April 2, 1840, in Paris to François Zola, an Italian engineer, and Émilie Aubert, a Frenchwoman[1†][2†][4†]. His father, originally named Francesco Zolla, was responsible for engineering the Zola Dam in Aix-en-Provence[1†][2†][4†]. The family moved to Aix-en-Provence when Émile was three years old[1†][2†][4†]. Tragically, his father died in 1847, leaving the family in financial hardship[1†][2†][4†]. Zola’s mother, determined to provide for her son, moved them to Paris in 1858[1†][2†][4†].

In Paris, Zola attended the Lycée Saint-Louis but struggled academically, failing his baccalauréat examination twice[1†][2†][4†]. Despite these setbacks, he found solace in writing and began his literary career while working various low-paying jobs[1†][2†][4†]. In 1865, Zola met Éléonore-Alexandrine Meley, a seamstress who became his lifelong partner[1†][2†][4†]. They married on May 31, 1870, and although their marriage remained childless, Alexandrine played a crucial role in supporting Zola’s career[1†][2†][4†].

Zola’s personal life took a dramatic turn when he began an affair with Jeanne Rozerot, a housemaid, in 1888[1†][2†][4†]. This relationship resulted in two children, Denise and Jacques[1†][2†][4†]. Despite the scandal, Zola continued to support Jeanne and their children, maintaining a delicate balance between his responsibilities to Alexandrine and his new family[1†][2†][4†]. Alexandrine eventually accepted Jeanne and the children, ensuring they were provided for after Zola’s death[1†][2†][4†].

Zola’s personal philosophy was deeply intertwined with his professional work, advocating for social justice and political liberalization[1†][2†][4†]. His involvement in the Dreyfus Affair, particularly through his open letter "I Accuse...!" (J’Accuse…!), exemplified his commitment to truth and justice[1†][2†][4†]. This advocacy extended to his personal relationships, where he demonstrated a profound sense of duty and care for those close to him[1†][2†][4†].

Zola’s life was marked by both personal and professional challenges, yet he remained steadfast in his pursuit of literary excellence and social reform[1†][2†][4†]. His legacy is not only defined by his contributions to literature but also by his unwavering dedication to his family and his principles[1†][2†][4†].

Conclusion and Legacy

Émile Zola’s impact on literature and society is profound and enduring[1†][2†][4†]. As the foremost practitioner of naturalism, his works provided a meticulous and unflinching portrayal of contemporary life, influencing countless writers and establishing a new literary standard[1†][2†][4†]. His 20-novel series, "The Rougon-Macquart" (Les Rougon-Macquart), remains a monumental achievement in literary history, offering a comprehensive exploration of French society during the Second Empire[1†][2†][4†]. Zola’s commitment to social justice is epitomized by his involvement in the Dreyfus Affair, where his open letter "I Accuse...!" (J’Accuse…!) played a pivotal role in exonerating Alfred Dreyfus and highlighting the pervasive anti-Semitism in French society[1†][2†][4†]. This act of courage solidified his legacy as a champion of truth and justice[1†][2†][4†].

Zola’s influence extends beyond literature into the realms of politics and social reform[1†][2†][4†]. His works often addressed issues such as poverty, industrialization, and the struggles of the working class, prompting readers to confront the harsh realities of their world[1†][2†][4†]. His dedication to depicting the human condition with honesty and empathy has earned him a lasting place in the literary canon[1†][2†][4†]. Today, Zola is remembered not only for his literary contributions but also for his unwavering commitment to social justice and his role in shaping modern French identity[1†][2†][4†].

Zola’s legacy is preserved through numerous adaptations of his works in film, theatre, and television, ensuring that his stories continue to reach new audiences[1†][2†][4†]. His influence is also evident in the continued study and appreciation of naturalism in literature courses worldwide[1†][2†][4†]. Monuments, museums, and academic institutions dedicated to his memory further attest to his enduring significance[1†][2†][4†]. Zola’s life and work remain a testament to the power of literature to effect social change and to the enduring importance of standing up for one’s beliefs[1†][2†][4†].

Key Information

- Also Known As: Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola[1†][2†][4†].

- Born: April 2, 1840, Paris, France[1†][2†][4†].

- Died: September 29, 1902, Paris, France[1†][2†][4†].

- Nationality: French[1†][2†][4†].

- Occupation: Novelist, journalist, playwright[1†][2†][4†].

- Notable Works: "The Rougon-Macquart" (Les Rougon-Macquart), "Thérèse Raquin", "Germinal", "Nana", "I Accuse...!" (J’Accuse…!)[1†][2†][4†].

- Notable Achievements: Major figure in the political liberalization of France, instrumental in the exoneration of Alfred Dreyfus, nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1901 and 1902[1†][2†][4†].

References and Citations:

- Wikipedia (English) - Émile Zola [website] - link

- Britannica - Émile Zola: French author [website] - link

- The Famous People - Emile Zola Biography [website] - link

- Wikipedia (Portugués) - Émile Zola [website] - link

- Goodreads - Author: Books by Émile Zola (Author of Germinal) [website] - link

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; additional terms may apply.

Ondertexts® is a registered trademark of Ondertexts Foundation, a non-profit organization.