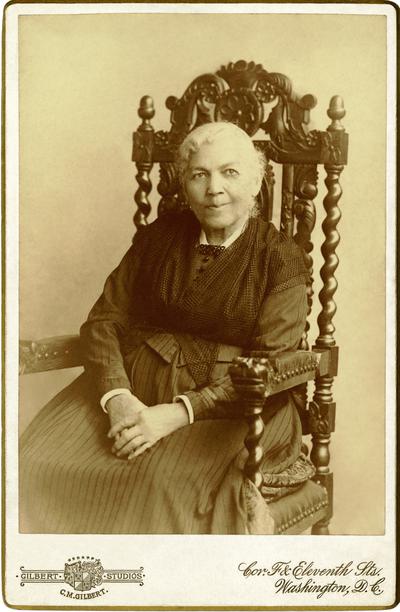

Harriet Jacobs

Harriet Jacobs[1†]

Harriet Jacobs[1†]Harriet Jacobs (1813 or 1815 – March 7, 1897) was an African-American abolitionist and writer[1†][2†][3†]. Her autobiography, “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” published in 1861 under the pseudonym Linda Brent, is now considered an "American classic"[1†][2†][3†].

Born into slavery in Edenton, North Carolina, Jacobs was sexually harassed by her enslaver[1†][2†][3†]. She managed to escape to the free North after hiding for seven years in a tiny crawl space under the roof of her grandmother’s house[1†]. In the North, she was reunited with her children Joseph and Louisa Matilda and her brother John S. Jacobs[1†].

Jacobs found work as a nanny and got into contact with abolitionist and feminist reformers[1†]. Even in New York City, her freedom was in danger until her employer was able to pay off her legal owner[1†]. During and immediately after the American Civil War, she travelled to Union-occupied parts of the Confederate South together with her daughter, organizing help and founding two schools for fugitive and freed slaves[1†].

Early Years and Education

Harriet Jacobs was born in 1813 in Edenton, North Carolina[1†]. She was born into a family enslaved by the Horniblow family, who owned a local tavern[1†]. Her mother was Delilah Horniblow, and her father was Elijah Knox, an enslaved man who enjoyed some privileges due to his skill as an expert carpenter[1†]. Harriet’s maternal grandmother, Molly Horniblow, had been freed by her white father, who also was her owner. But she had been kidnapped, and had no chance for legal protection because of her dark skin[1†].

Harriet was taught to read and sew at an early age[1†][2†][4†][5†]. These skills were taught by her white mistress, Elizabeth Horniblow[1†][5†]. After the death of her beloved mother, Harriet formed a bond with her grandmother, Molly Horniblow[1†][2†]. When Elizabeth Horniblow died, Harriet, who was six years old at the time, was left to her young niece, Mary Matilda Norcom[1†][5†].

Harriet’s father died in 1826[1†]. After his death, Harriet and her brother John used the opportunity of the baptism of her children to register Jacobs as their family name[1†]. The baptism was conducted without the knowledge of Harriet’s master, Norcom[1†].

Career Development and Achievements

Harriet Jacobs’s career was marked by her resilience and determination to fight against the injustices of slavery[2†][1†][6†]. After escaping from her enslaver, she found work as a nanny in New York City[2†][1†]. She eventually moved to Rochester, New York, to work in the antislavery reading room above abolitionist Frederick Douglass’s newspaper, The North Star[2†].

During an abolitionist lecture tour with her brother, Jacobs began her lifelong friendship with the Quaker reformer Amy Post[2†]. Encouraged by Post and others, Jacobs wrote the story of her enslavement[2†]. Self-published in 1861, “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl” is arguably the most comprehensive slave narrative written by a woman[2†]. Writing as Linda Brent, Jacobs detailed the sexual abuse of enslaved women and the anguish felt by enslaved mothers, who frequently experienced the loss of their children[2†].

Jacobs’s book did not receive much acclaim during the Civil War; however, she continued working as an abolitionist and writing letters to the editor and publishing essays in various periodicals such as American Baptist[2†][7†]. After the war, Jacobs joined the American Equal Rights Association and promoted education for freedmen[2†][7†].

During and immediately after the American Civil War, she travelled to Union-occupied parts of the Confederate South together with her daughter, organizing help and founding two schools for fugitive and freed slaves[2†][1†].

First Publication of Her Main Works

Harriet Jacobs is best known for her autobiography, “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself” (1861), published under the pseudonym Linda Brent[2†][1†]. This work is now considered an “American classic” and is one of the few slave narratives written by a Black woman[2†][4†].

In her autobiography, Jacobs provides a detailed account of the sexual abuse of enslaved women and the anguish felt by enslaved mothers, who frequently experienced the loss of their children[2†]. Jacobs’s narrative is an eloquent and uncompromising depiction of her experiences, making it a significant contribution to the literature of the period[2†].

The book was edited by white abolitionist Lydia Maria Child and published in 1852[2†][8†]. In her writing, Jacobs put an individual face on major social and political events of her era, particularly one of the most inhumane aspects of enslaved womanhood, sexual abuse, and molestation by white men[2†][4†].

Here is a brief summary of her main work:

- “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself” (1861): This autobiography is a detailed account of Jacobs’s life as a slave, her sexual abuse, and the anguish she felt as a mother. It provides an individual perspective on the major social and political events of her era, particularly focusing on the sexual abuse and molestation of enslaved women by white men[2†][1†][8†][4†].

Analysis and Evaluation

Harriet Jacobs’s autobiography, “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself”, is a significant work that provides a broad picture of life as a woman, a victim of abuse, and a Black American in the South during the early to mid-Nineteenth century[9†]. The narrative is colored and dominated by her experience as a slave[9†].

Jacobs was examining realities that could not yet be uttered in polite society[9†][10†]. Her use of sentimental language common to women’s fiction in the Victorian era, her avoidance of direct description of nudity and sexuality, and her emphasis on the venerated cultural role of motherhood enabled her to lodge her critique[9†][10†]. This approach allowed her to discuss the sexual abuse of enslaved women and the anguish felt by enslaved mothers, who frequently experienced the loss of their children[9†][2†][1†].

Her work is an eloquent and uncompromising slave narrative[9†][2†][1†]. It puts an individual face on major social and political events of her era, particularly one of the most inhumane aspects of enslaved womanhood, sexual abuse, and molestation by white men[9†][11†].

Jacobs’s narrative is a fearless truthtelling that provides a comprehensive view of the realities of slavery, making it a significant contribution to the literature of the period[9†][2†][1†][10†].

Personal Life

Harriet Jacobs was born into slavery in 1813 in Edenton, North Carolina[1†][2†]. Her parents were Delilah Horniblow, who was enslaved by the Horniblow family, and Elijah Knox, also enslaved but enjoyed some privileges due to his skill as an expert carpenter[1†]. After her parents’ death, Harriet and her brother John were raised by their maternal grandmother, Molly Horniblow[1†][2†].

In her teens, Harriet became involved with a young white lawyer named Samuel Tredwell Sawyer[1†][7†]. Their relationship resulted in the birth of two children[1†][2†]. Harriet’s decision to enter into a relationship with Sawyer was a form of resistance against her enslaver, who had been sexually harassing and abusing her[1†][7†].

Harriet spent seven years hiding in a tiny crawl space under the roof of her grandmother’s house to escape her enslaver and protect her children[1†]. During this time, her children were bought by their father and later sent to the North[1†][2†].

After escaping to the North in 1842, Harriet worked as a nanny in New York City[1†][2†]. Even in New York, her freedom was in danger until her employer was able to pay off her legal owner[1†]. She later moved to Rochester, New York, to work in the antislavery reading room above abolitionist Frederick Douglass’s newspaper, The North Star[1†][2†].

Throughout her life, Harriet Jacobs faced numerous challenges, including harassment from her former owner and the constant threat of recapture until the end of the Civil War[1†][12†]. Despite these hardships, she managed to build a career as a political writer and speaker, all while struggling to provide for her family[1†][12†].

Conclusion and Legacy

Harriet Jacobs’ life and work have left a lasting legacy. Her autobiography, “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” is considered an “American classic” and a significant contribution to the abolitionist movement[1†][13†]. It is one of the few slave narratives written by a Black woman and provides a unique perspective on the lived experiences of enslaved women in the United States[1†][14†].

Jacobs’ narrative is not just a testament to her personal strength and resilience but also a powerful indictment of the institution of slavery[1†]. Her work continues to be a significant resource for understanding the lived experiences of enslaved women in the United States[1†][14†].

Her story illustrates the resilience and strength of enslaved women and the myriad ways they resisted enslavement[1†][15†]. Despite the numerous challenges she faced, including harassment from her former owner and the constant threat of recapture until the end of the Civil War, Jacobs managed to build a career as a political writer and speaker, all while struggling to provide for her family[1†][15†].

Jacobs’ legacy continues to inspire and educate people about the realities of slavery and the extraordinary courage of those who resisted it[1†][14†][15†][13†][16†].

Key Information

- Also Known As: Harriet A. Jacobs, Harriet Ann Jacobs, Linda Brent[2†]

- Born: February 11, 1813, in Edenton, North Carolina[2†][14†]

- Died: March 7, 1897, in Washington, D.C[2†][14†]

- Nationality: American[2†]

- Occupation: Abolitionist, Autobiographer[2†]

- Notable Works: "Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself"[2†]

- Parents: Elijah Knox and Delilah Horniblow[2†][14†]

- Children: Louisa Matilda Jacobs, Joseph Jacobs[2†][14†]

References and Citations:

- Wikipedia (English) - Harriet Jacobs [website] - link

- Britannica - Harriet Jacobs: American abolitionist and author [website] - link

- Wikiwand - Harriet Jacobs - Wikiwand [website] - link

- EDSITEment - Brief Biography of Harriet Jacobs [document] - link

- Americans Who Tell The Truth - Harriet Jacobs [website] - link

- Lighting the Way, Historic Women of the SouthCoast - Harriet Jacobs [website] - link

- North Carolina History Project - Harriet Jacobs (1813-1897) [website] - link

- BlackPast - Harriet Jacobs (1813-1897) • [website] - link

- 123HelpMe - Harriet Jacobs Analysis - 1371 Words [website] - link

- Literary Hub - The Fearless Truthtelling of Harriet Ann Jacobs ‹ Literary Hub [website] - link

- University of Texas Press - Behind the Resilience of Harriet Jacobs: An Interview with Alyssa Bellows by Megan Marshall and Laura Franco [website] - link

- Goodreads - Book: Harriet Jacobs: A Life [website] - link

- Black History Month - Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacob [website] - link

- ThoughtCo - Biography of Harriet Jacobs, Writer and Abolitionist [website] - link

- Understanding the American South - Resistance, Resilience, & Strength: The Life of Harriet Ann Jacobs [website] - link

- Spectrum News 1 - Black History Month: The legacy of Harriet Ann Jacobs [website] - link

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; additional terms may apply.

Ondertexts® is a registered trademark of Ondertexts Foundation, a non-profit organization.