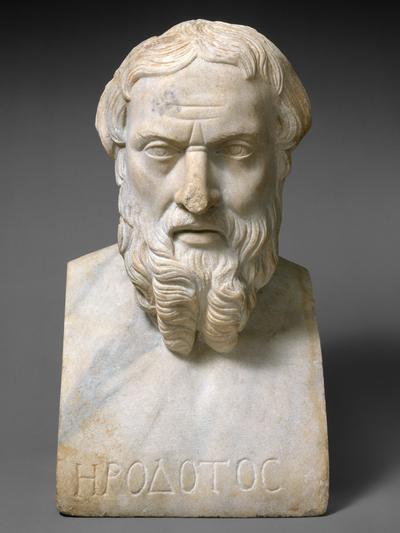

Herodotus

Herodotus[1†]

Herodotus[1†]Herodotus, often called “The Father of History,” was a Greek historian and geographer from Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), born around 484 BC and dying around 430–420 BC. He wrote the Histories, the first great narrative history, detailing the Greco-Persian Wars. Despite criticism for including legends, much of his work has been validated by modern historians. Herodotus's Histories also explore cultural, ethnographical, geographical, and historiographical contexts, enriching the narrative with extensive background information[1†][2†].

Early Years and Education

Herodotus was born around 484 BC in Halicarnassus, a Greek city in southwest Asia Minor that was then under Persian rule[2†][3†]. The exact date of his birth is uncertain[2†][3†]. He was the son of Lyxes and Dryo, and he had a brother named Theodorus[2†][3†]. He was also related to Panyassis, an epic poet of the time[2†][3†].

Herodotus came from a relatively wealthy and influential family[2†][4†][5†]. His family’s influence is believed to have provided him with an excellent education[2†][4†]. His writings reveal a love for the island of Samos, which suggests that he might have lived there during his youth[2†][3†]. There is a possibility that his family was involved in an uprising against Lygdamis, leading to a period of exile on Samos[2†][5†].

During his early years, Herodotus developed a keen interest in exploring various kingdoms and empires, which later played a significant role in his career as a historian[2†][3†]. His travels began as a young man, and he spent several years exploring far-off kingdoms and gaining extensive knowledge[2†][3†].

Career Development and Achievements

Herodotus’s career was primarily marked by his extensive travels and his work as a historian[2†][6†]. He journeyed to Egypt, Libya, Syria, Babylonia, Susa in Elam, Lydia, Phrygia, and even as far as the Ukraine[2†][6†]. He also traveled up the Hellespont to Byzantium, went to Thrace and Macedonia, and journeyed northward beyond the Danube and eastward along the northern shores of the Black Sea as far as the Don River[2†].

During his travels, Herodotus developed a keen interest in exploring various kingdoms and empires, which later played a significant role in his career as a historian[2†][6†]. These journeys took him many years and allowed him to gain extensive knowledge[2†][6†].

Herodotus is best known for writing the Histories, a detailed account of the Greco-Persian Wars[2†][6†]. His work is recognized as the first great narrative history produced in the ancient world[2†][6†]. He was the first writer to perform systematic investigation of historical events[2†][6†]. His work primarily covers the lives of prominent kings and famous battles such as Marathon, Thermopylae, Artemisium, Salamis, Plataea, and Mycale[2†][6†].

Despite being criticized for his inclusion of “legends and fanciful accounts” in his work, a sizable portion of the Histories has since been confirmed by modern historians and archaeologists[2†][6†]. Herodotus’s work deviates from the main topics to provide a cultural, ethnographical, geographical, and historiographical background that forms an essential part of the narrative and provides readers with a wellspring of additional information[2†][6†].

First Publication of His Main Works

Herodotus is renowned for his singular work, the Histories, which is considered the first great narrative history produced in the ancient world[2†][7†]. The Histories primarily cover the lives of prominent kings and famous battles such as Marathon, Thermopylae, Artemisium, Salamis, Plataea, and Mycale[2†][1†]. His work deviates from the main topics to provide a cultural, ethnographical, geographical, and historiographical background that forms an essential part of the narrative and provides readers with a wellspring of additional information[2†][1†].

The Histories is a unified artistic masterpiece, with many illuminating digressions and anecdotes skillfully worked into the narrative[2†][7†]. It is a record of the ancient traditions, politics, geography, and clashes of various cultures that were known in Western Asia, Northern Africa, and Greece at that time[2†][3†].

The Histories is divided into nine books[2†]:

- Book I - Describes the origin of the Greco-Persian Wars.

- Book II - Contains a description of Egypt.

- Book III - Covers the reign of Cambyses, the son of Cyrus the Great, and the conspiracy of the Magi.

- Book IV - Discusses the Scythians.

- Book V - Describes the revolt of the Ionians and other happenings leading up to the war.

- Book VI - Covers the Battle of Marathon.

- Book VII - Chronicles the expedition of Xerxes.

- Book VIII - Discusses the battles of Artemisium and Salamis.

- Book IX - Covers the battles of Plataea and Mycale.

Herodotus’s Histories has it all: tales of war, eyewitness travel writing, notes on flora and fauna, and accounts of fantastic creatures such as winged snakes[2†][8†]. His stories share a common humanity that speaks to us, 2500 years on[2†][8†].

Analysis and Evaluation

Herodotus’s work, the Histories, is a foundational piece in the historical tradition[9†]. It represents the first systematic attempt to break down the past into sequences of interactions between cause and effect[9†]. The term “History” is etymologically descended from the Greek word “historie” or “inquiry,” and Herodotus is the first person to delve into past inquiry to help understand and contextualize the present[9†].

His work attempts to break through the subjective fog of historical evidence and textual artifacts and approximate its “real” sequence of events[9†]. This lofty goal intersects with the literary context of the time, crossing paths with Homeric epics, Sophist thought, and lyric poetry[9†]. Major works of the Greek literary canon find their way into Herodotus’s retelling of events, and these conventional ways of telling stories and communicating information litter the Histories[9†].

However, Herodotus’s insight into the events he retells is often marred by inaccuracies, fiction, gossip, and mythologization[9†]. The validity of his claims has been questioned time and again by scholars across many fields and areas of study[9†]. Despite this, his narrative features enough proven facts, accurate assessments, and unexpected insight into the era to be accepted by historians and scholars[9†].

Despite its less-than-historiographical methods, the Histories is an unparalleled work, for it was a prototypical effort in true history writing[9†]. Moreover, Herodotus’s “inquiries” was a novel means of seeking and providing accurate sources and empirically-proven evidence to validate his claims[9†]. His effort inspired the historical methodology to come and wrought an important change in the genre[9†].

Personal Life

Herodotus was born around 484 BC in Halicarnassus, Caria, Asia Minor, within the Persian Empire (modern-day Bodrum, Turkey)[2†][1†]. He was the son of Lyxes and Dryo, and the brother of Theodorus[2†][1†][10†]. He was also related to Panyassis, an epic poet of the time[2†][1†][10†].

Herodotus’s life is shrouded in mystery, and much of what we know about him comes from his own writings[2†][1†][10†]. It is believed that he came from a relatively wealthy family[2†][5†]. He was exiled from Halicarnassus by the tyrant Lygdamis and lived in Samos until he returned to assist in the removal of his foe[2†][5†]. He spent time in Athens and even joined the colony of Thurii[2†][5†].

Herodotus was a wide traveler. His longer wanderings covered a large part of the Persian Empire: he went to Egypt, at least as far south as Elephantine (Aswān), and he also visited Libya, Syria, Babylonia, Susa in Elam, Lydia, and Phrygia[2†]. He journeyed up the Hellespont (now Dardanelles) to Byzantium, went to Thrace and Macedonia, and traveled northward to beyond the Danube and to Scythia eastward along the northern shores of the Black Sea as far as the Don River and some way inland[2†]. These travels would have taken many years[2†].

Conclusion and Legacy

Herodotus had his predecessors in prose writing, especially Hecataeus of Miletus, a great traveler whom Herodotus mentions more than once[11†]. But these predecessors, for all their charm, wrote either chronicles of local events, of one city or another, covering a great length of time, or comprehensive accounts of travel over a large part of the known world, none of them creating a unity, an organic whole[11†].

In the sense that he created a work that is an organic whole, Herodotus was the first of Greek, and so of European, historians[11†]. His work is not only an artistic masterpiece; for all his mistakes (and for all his fantasies and inaccuracies) he remains the leading source of original information not only for Greek history of the all-important period between 550 and 479 BCE but also for much of that of western Asia and of Egypt at that time[11†][2†].

Herodotus sensibly declared that he did not believe all that he had been told. He arrived at his conclusions after sifting his sources and comparing them[11†][12†]. The Histories likely constitutes Herodotus’ life’s work. Given the resources he had at his disposal, it was an outstanding achievement[11†][12†].

Key Information

- Also Known As: Heródoto, The Father of History[1†]

- Born: Around 484 BC, Halicarnassus, Caria, Asia Minor, Persian Empire (modern-day Bodrum, Turkey)[1†][2†][1†]

- Died: Around 430–420 BC[1†][2†][1†]

- Nationality: Greek[1†][2†][1†]

- Occupation: Historian[1†][2†][1†]

- Notable Works: The Histories – a detailed account of the Greco-Persian Wars[1†][2†][1†]

- Notable Achievements: Herodotus is recognized as the author of the first great narrative history produced in the ancient world[1†][2†][1†]. He is known for his systematic investigation of historical events[1†].

References and Citations:

- Wikipedia (English) - Herodotus [website] - link

- Britannica - Herodotus: Greek historian [website] - link

- The Famous People - Herodotus Biography [website] - link

- History Hit - The ‘Father of History’: Who Was Herodotus? [website] - link

- Brown University - Herodotus [website] - link

- The History Junkie - Herodotus Facts, Works, and Accomplishments [website] - link

- Britannica - Herodotus summary [website] - link

- The Conversation - Guide to the classics: The Histories, by Herodotus [website] - link

- eNotes - The History of Herodotus Analysis [website] - link

- MetaUnfolded.com - Herodotus Bio, Early Life, Career, Net Worth and Salary [website] - link

- Britannica - Herodotus - Father of History, Historian, Greek [website] - link

- JW.ORG - Jehovah’s Witnesses - Herodotus, “Father of History”—His Legacy, “The Histories” [website] - link

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; additional terms may apply.

Ondertexts® is a registered trademark of Ondertexts Foundation, a non-profit organization.