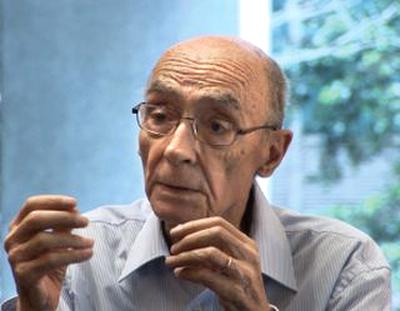

José Saramago

José Saramago[4†]

José Saramago[4†]José Saramago, born on November 16, 1922, in Azinhaga, Portugal, was a renowned Portuguese novelist and man of letters[1†]. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1998[1†]. Saramago was born into a family of landless peasants and grew up in great poverty in Lisbon[1†][2†][1†][3†]. His parents were José de Sousa and Maria da Piedade[1†][2†]. The name “Saramago” was added by the civil registry official, which was the nickname his father’s family was known by in the village[1†][2†].

Early Years and Education

José Saramago was born on November 16, 1922, in Azinhaga, a small village in the Portuguese province of Ribatejo, about 100 kilometers northeast of Lisbon[4†][5†]. He was born into a family of landless peasants[4†][5†]. His parents were José de Sousa and Maria da Piedade[4†]. The family moved to Lisbon in 1924, where his father found employment as a police officer[4†][6†][7†].

Saramago’s early education was marked by economic hardships. Despite being a good student, he had to leave grammar school at the age of 12 as his parents could not afford to pay for his education[4†][6†][5†]. He was then enrolled in a technical school where he learned the trade of a mechanical locksmith[4†].

During his holidays, he would spend time with his illiterate grandparents, who introduced him to folklore and fantasy[4†][6†]. These experiences played a significant role in shaping his imagination and literary interest[4†][6†][7†].

After completing his education, Saramago took up various jobs to sustain his living. He worked as a car mechanic, metalworker, translator, journalist, and assistant editor of a newspaper[4†][6†]. It was during this time that he began to nurture his literary interests[4†][6†][7†].

Career Development and Achievements

José Saramago began his career in various jobs, including as a car mechanic, metalworker, translator, journalist, and assistant editor of a newspaper[8†][1†]. He also worked as a draughtsman and health and social worker[8†][9†]. His first novel, “Land of Sin”, was published in 1947[8†][9†]. However, it took him another 19 years to publish his second book, a volume of poetry called “Possible Poems”[8†][9†].

Saramago became a full-time author in his fifties[8†][1†]. His international breakthrough came with the novel “Baltasar and Blimunda”, published in 1982[8†][10†]. This novel, set in 18th century Portugal, is a blasphemous and humorous love story that chronicles the efforts of a handicapped war veteran and his lover to flee their situation by using a flying machine powered by human will[8†][1†].

Saramago was politically involved in the Communist Party in Portugal, which is reflected in his literary output[8†]. His writings were controversial in his native country, and consequently, Saramago came to settle on Lanzarote later in life[8†][10†].

In 1998, Saramago was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature[8†][1†][8†]. The Nobel committee described him as a writer "who with parables sustained by imagination, compassion and irony continually enables us once again to apprehend an elusive reality"[8†].

Saramago’s oeuvre totals 30 works, and comprises not only prose but also poetry, essays, and drama[8†][10†]. His style is characterized by the blending of dialog and narration, with sparse punctuation and long sentences that can extend for several pages[8†].

First Publication of His Main Works

José Saramago’s literary journey began with his first novel, “Land of Sin”, which was published in 1947[4†][9†]. However, it took him another 19 years to publish his second book, a volume of poetry called “Possible Poems” in 1966[4†][9†]. His literary output was regular and wide-ranging, encompassing fields as varied as poetry, novels, short stories, and plays[4†][9†].

In 1977, Saramago published what he considers to be his first novel, "Manual of Painting and Calligraphy"[4†][11†]. This was followed by two more books in quick succession: “Quasi Objects” in 1978 and “Raised from the Ground” in 1980[4†][11†].

One of Saramago’s most important novels is “Memorial do convento” (1982; “Memoirs of the Convent”; Eng. trans. Baltasar and Blimunda)[4†][1†]. With 18th-century Portugal (during the Inquisition) as a backdrop, it chronicles the efforts of a handicapped war veteran and his lover to flee their situation by using a flying machine powered by human will[4†][1†].

Another ambitious novel, “O ano da morte de Ricardo Reis” (1984; The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis), juxtaposes the romantic involvements of its narrator, a poet-physician who returns to Portugal at the start of the Salazar dictatorship, with long dialogues that examine human nature as revealed in Portuguese history and culture[4†][1†].

His other notable works include “The Gospel According to Jesus Christ” (1991), “Blindness” (1995), “All the Names” (1997), “The Double” (2002), “Death with Interruptions” (2005), and “Cain” (2009)[4†].

Analysis and Evaluation

José Saramago’s works are often described as fantastic and surreal[12†]. His characters, as well as his readers, are compelled to confront the basis for the existence of humanity, questioning what it means to be human in ever-changing modern civilizations[12†]. His characters grapple with finding meaning at precisely the moment of greatest change in their respective social settings[12†].

One of the key aspects of Saramago’s work is his use of language. A study on his novel “Blindness” illuminates appraisal theory as a tool for analyzing the novel[12†][13†]. The study reveals that the novel’s opening displays a high frequency of pessimistic attitudes[12†][13†]. This reflects Saramago’s ability to evoke strong emotions and attitudes through his writing.

Saramago’s work also reflects his political beliefs and his views on society. A growing pessimism towards the idea of a socialist utopia arising as the result of organized revolutionary movements is noted in his work[12†][14†]. However, this is counterbalanced by the simultaneous presentation of ‘radical “micro-politics”’ within personal, everyday interactions[12†][14†]. This reflects Saramago’s conviction that the road to utopia must involve mistakes[12†][14†].

In summary, Saramago’s work is characterized by its fantastic and surreal nature, its exploration of the human condition, its evocative use of language, and its reflection of Saramago’s political and societal views.

Personal Life

José Saramago was first married to Ilda Reis in 1944[4†][6†][15†][16†]. The couple had one child, a daughter named Violante, born in 1947[4†][6†][15†][16†]. However, their marriage ended in divorce in 1970[4†].

After his divorce, Saramago was in a relationship with Isabel da Nóbrega[4†]. The relationship lasted from 1968 to 1986[4†].

In 1988, Saramago married Spanish journalist Pilar del Río[4†][17†]. They lived together on the Spanish island of Lanzarote until Saramago’s death in 2010[4†].

Saramago was known for his strong political beliefs. He joined the Portuguese Communist Party in 1969[4†] and was a proponent of libertarian communism[4†]. He was also an atheist and defended love as an instrument to improve the human condition[4†].

Conclusion and Legacy

José Saramago, born into a family of landless peasants, rose to become a Nobel-laureate Portuguese writer, playwright, and journalist[18†][19†]. His works, some of which can be seen as allegories, commonly present subversive perspectives on historic events, emphasizing the human factor rather than the officially sanctioned story[18†][19†]. Saramago was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1998[18†][19†].

Saramago’s work became noted for its artistic invention, experimentation, and originality[18†][20†]. He also gained a reputation for introducing dark and dissident editorials into his work, which occasionally created controversy in a Portuguese society in which political and religious conservatives still held much power and influence[18†][20†].

A growing pessimism on Saramago’s part towards the idea of a socialist utopia arising as the result of organized revolutionary movements is also noted[18†][14†]. This was counterbalanced by the simultaneous presentation of ‘radical “micro-politics”’ within personal, everyday interactions, and the titular ‘necessity of error’ resulting from Saramago’s conviction that the road to utopia must involve mistakes[18†][14†].

On the one hand, Saramago’s narrative may be discussed within a broader phenomenological framework, whose main topics include the space for a tactile and bodily knowledge, man’s freedom and responsibility, and the relationship between reality and the virtuality of experience[18†][21†].

Key Information

- Also Known As: José de Sousa Saramago[1†][8†]

- Born: November 16, 1922, Azinhaga, Portugal[1†][8†]

- Died: June 18, 2010, Lanzarote, Canary Islands, Spain[1†][8†]

- Nationality: Portuguese[1†][8†]

- Occupation: Novelist, short-story writer[1†][22†]

- Notable Works: “Baltasar and Blimunda”, “Blindness”, “Claraboia”, “The Gospel According to Jesus Christ”, "The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis"[1†]

- Notable Achievements: Nobel Prize in Literature, 1998[1†][8†]

References and Citations:

- Britannica - José Saramago: Portuguese author [website] - link

- José Saramago Foundation - Biography [website] - link

- Discover Walks Blog - The Life and Works of Portuguese José Saramago [website] - link

- Wikipedia (English) - José Saramago [website] - link

- RFI - The life of Jose Saramago [website] - link

- The Famous People - José Saramago Biography [website] - link

- The Guardian - José Saramago obituary [website] - link

- The Nobel Prize - José Saramago – Facts [website] - link

- Visit Lisboa - Biography José Saramago - Saramago Route [website] - link

- The Nobel Prize - The Nobel Prize for Literature 1998 - Bio-bibliography [website] - link

- Encyclopedia.com - Saramago, José [website] - link

- eNotes - José Saramago Critical Essays [website] - link

- Academia - The Language of Evaluation in Jose Saramago's Blindness via Appraisal Theory [website] - link

- Oxford Academic - Forum for Modern Language Studies - Sabine, Mark. José Saramago: History, Utopia, and the Necessity of Error [website] - link

- Simple Wikipedia (English) - José Saramago [website] - link

- eNotes - José Saramago Biography [website] - link

- CelebsAgeWiki - José Saramago Biography, Age, Height, Wife, Net Worth, Family [website] - link

- Britannica - José Saramago summary [website] - link

- New World Encyclopedia - Jose Saramago [website] - link

- eNotes - José Saramago World Literature Analysis [website] - link

- Springer Link - Saramago’s Philosophical Heritage - Chapter: Some Remarks on a Phenomenological Interpretation of Saramago’s [website] - link

- Infoplease - Saramago, José [website] - link

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; additional terms may apply.

Ondertexts® is a registered trademark of Ondertexts Foundation, a non-profit organization.