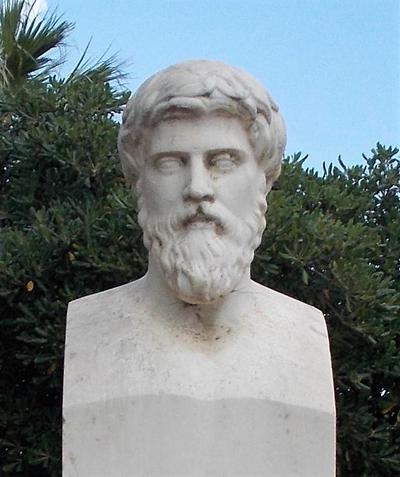

Plutarch

Plutarch[1†]

Plutarch[1†]Plutarch, also known as Plutarco, Plutarchos and Plutarchus, was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi[1†]. He was born around 46 CE in the small town of Chaeronea, in the Greek region known as Boeotia[1†][2†]. His works have had a profound influence on the evolution of the essay, biography, and historical writing in Europe from the 16th to the 19th century[1†][3†].

Among his approximately 227 works, the most significant are the “Parallel Lives”, where he recounts the noble deeds and characters of Greek and Roman soldiers, legislators, orators, and statesmen, and the “Moralia”, or “Ethica”, a series of more than 60 essays on ethical, religious, physical, political, and literary topics[1†][3†].

Plutarch’s writings have had a lasting impact on literature and history, and his works continue to be studied and revered for their historical value and insight into ancient cultures[1†][3†].

Early Years and Education

Plutarch was born around 46 CE in the small town of Chaeronea, in the Greek region known as Boeotia[3†][1†]. He was born into a prominent family; his father, Aristobulus, was a biographer and philosopher[3†][1†]. His family was long established in the town, and his grandfather was named Lamprias[3†][1†]. His name is a compound of the Greek words πλοῦτος, “wealthy” and ἀρχός, “leader,” reflecting the traditional aspirational Greek naming convention[3†][1†].

In 66-67 CE, Plutarch studied mathematics and philosophy at Athens under the philosopher Ammonius[3†][1†]. His education in Athens, a major center of learning in the ancient world, likely had a significant influence on his later works[3†][2†]. He never became a staunch Platonist, but remained open to the ideas of other philosophical schools such as the Stoa and the school of Aristotle[3†][2†].

Public duties later took him several times to Rome, where he lectured on philosophy, made many friends, and perhaps enjoyed the acquaintance of the emperors Trajan and Hadrian[3†]. His time in Rome not only broadened his intellectual horizons but also provided him with valuable insights into the Roman way of life and thinking, which is reflected in his "Parallel Lives"[3†].

Career Development and Achievements

Plutarch’s career was marked by a blend of philosophical and historical pursuits, and he made significant contributions to both fields[3†][1†].

After studying mathematics and philosophy in Athens, Plutarch traveled widely, visiting central Greece, Sparta, Corinth, Patrae (Patras), Sardis, and Alexandria[3†]. He made his normal residence at Chaeronea, where he held the chief magistracy and other municipal posts, and directed a school with a wide curriculum in which philosophy, especially ethics, occupied the central place[3†].

His public duties took him several times to Rome, where he lectured on philosophy, made many friends, and perhaps enjoyed the acquaintance of the emperors Trajan and Hadrian[3†][1†]. According to the Suda lexicon, Trajan bestowed the high honor of ornamenta consularia upon him[3†]. He also possessed Roman citizenship, his family name, Mestrius, was adopted from his friend Lucius Mestrius Florus, a Roman consul[3†][1†].

Plutarch’s literary output was immense, but his popularity rests primarily on his “Parallel Lives”, a series of pairs of biographies of famous Greeks and Romans, and the “Moralia”, a series of more than 60 essays on ethical, religious, physical, political, and literary topics[3†][1†][4†]. His works strongly influenced the evolution of the essay, the biography, and historical writing in Europe from the 16th to the 19th century[3†][5†].

First Publication of His Main Works

Plutarch’s most significant works are “Parallel Lives” and “Moralia” which have had a profound influence on literature and philosophy[3†][1†].

- Parallel Lives (Bioi parallēloi): This is a series of biographies of illustrious Greeks and Romans, arranged in pairs to illuminate their common moral virtues and vices[3†][1†]. Rather than being a historical account, it provides more of an insight into human nature[3†][1†]. The work recounts the noble deeds and characters of Greek and Roman soldiers, legislators, orators, and statesmen[3†].

- Moralia (Ethica): This is a collection of more than 60 essays on various topics including ethical, religious, physical, political, and literary subjects[3†][1†]. In one of his essays, he shows his profound admiration for Plato by discussing Plato’s Timaeus in his treatise De animae procreation in Timaeo[3†][6†].

These works not only showcase Plutarch’s extensive knowledge and understanding of various subjects but also his ability to present them in an engaging and insightful manner. His writings continue to be studied and admired for their depth and clarity[3†][1†].

Analysis and Evaluation

Plutarch’s works, particularly “Parallel Lives” and “Moralia,” have had a profound influence on the evolution of essay writing, biography, and historical writing from the 16th to the 19th century in Europe[3†]. His writings are not merely historical accounts but provide deep insights into human nature[3†][7†].

In “Parallel Lives,” Plutarch presents the biographies of illustrious Greeks and Romans in pairs, illuminating their common moral virtues and vices[3†][7†]. This approach provides a basis for comparing ancient Greek and Roman cultures[3†][7†]. His interest in inculcating moral principles is evident in his works[3†][7†].

“Moralia,” a collection of more than 60 essays on various topics, offers insights into the psychology, education, morality, and cultural identity of ancient Greece and Rome[3†][7†]. Plutarch’s philosophical views, particularly his model of double causation, are evident in his analysis of the operation and functioning of oracles[3†][8†].

Plutarch’s works have been widely studied and referenced in Western intellectual traditions[3†][9†]. His writings have been used by many, including William Shakespeare, who made use of Sir Thomas North’s sixteenth-century translation of Plutarch[3†][7†].

Plutarch’s writings reflect his firm grasp of scholarship, his ability to correct errors, and his enthusiasm for his subjects[3†][7†]. His works continue to be admired for their depth, clarity, and insightful analysis[3†][7†].

Personal Life

Plutarch was born to a prominent family in the small town of Chaeronea, Boeotia[1†]. His father was named Aristobulus, who was also a biographer and philosopher[1†][3†][1†]. He had brothers named Timon and Lamprias, who are frequently mentioned in his essays and dialogues[1†].

Plutarch was married to a woman named Timoxena, and they had at least five children[1†]. Unfortunately, two of their children, a daughter named Timoxena after her mother, and a young son named Chaeron, died in childhood[1†]. Plutarch’s letter to his wife, Timoxena, consoling her on the death of their infant daughter, hints at a belief in reincarnation[1†].

Two of their sons, named Autoboulos and Plutarch, appear in a number of Plutarch’s works[1†]. Plutarch’s treatise on Plato’s Timaeus is dedicated to them[1†]. It is likely that a third son, named Soklaros after Plutarch’s confidant Soklaros of Tithora, survived to adulthood as well[1†].

Plutarch studied mathematics and philosophy in Athens under the philosopher Ammonius[1†][4†]. He attended the games of Delphi where the emperor Nero competed and possibly met prominent Romans, including the future emperor Vespasian[1†].

Conclusion and Legacy

Plutarch’s influence has been profound and enduring. His works, especially those on philosophy and education, continued to be highly regarded and popular in Late Antiquity by scholars and early Christians, in the Byzantine period, and the Renaissance[10†]. His writings, particularly the “Parallel Lives” and “Moralia”, strongly influenced the evolution of the essay, the biography, and historical writing in Europe from the 16th to the 19th century[10†][3†][10†].

Plutarch was loved and respected in his own time and in later antiquity[10†][11†]. His “Lives” inspired a rhetorician, Aristides, and a historian, Arrian, to write similar comparisons[10†][11†]. A copy of his works even accompanied the emperor Marcus Aurelius when he took the field against the Marcomanni[10†][11†].

In conclusion, Plutarch’s works have left a lasting impact on literature, history, and philosophy. His writings have provided valuable insights into the lives and times of important historical figures, offering a unique perspective on the events and cultures of the past[10†][3†][10†]. His legacy continues to be felt today, as his works remain a valuable resource for understanding the ancient world[10†].

Key Information

- Also Known As: Plutarco, Plutarchos, Plutarchus[3†]

- Born: 46 CE, Chaeronea, Boeotia, Greece[3†]

- Died: After 119 CE[3†]

- Nationality: Greek[3†]

- Occupation: Biographer, Author, Philosopher[3†]

- Notable Works: “Parallel Lives”, “Moralia” or "Ethica"[3†]

- Notable Achievements: Plutarch’s works have strongly influenced the evolution of the essay, the biography, and historical writing in Europe from the 16th to the 19th century[3†].

References and Citations:

- Wikipedia (English) - Plutarch [website] - link

- New World Encyclopedia - Plutarch [website] - link

- Britannica - Plutarch: Greek biographer [website] - link

- Great Thinkers - Biography - Plutarch [website] - link

- Britannica - Why is Plutarch important? [website] - link

- World History Edu - Plutarch – the great historian of antiquity who described Herodotus as the “Father of Lies” [website] - link

- eNotes - Plutarch Analysis [website] - link

- Bryn Mawr Classical Review - A Perfect Medium? Oracular Divination in the Thought of Plutarch. Plutarchea Hypomnemata – Bryn Mawr Classical Review [website] - link

- Cambridge University Press - Plutarch's Prism - Chapter: A Brief Introduction to Plutarch and a Comparison of Cicero and Plutarch on Public Ethics (Chapter 1) [website] - link

- World History - Plutarch [website] - link

- Britannica - Plutarch - Biographer, Historian, Philosopher [website] - link

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; additional terms may apply.

Ondertexts® is a registered trademark of Ondertexts Foundation, a non-profit organization.