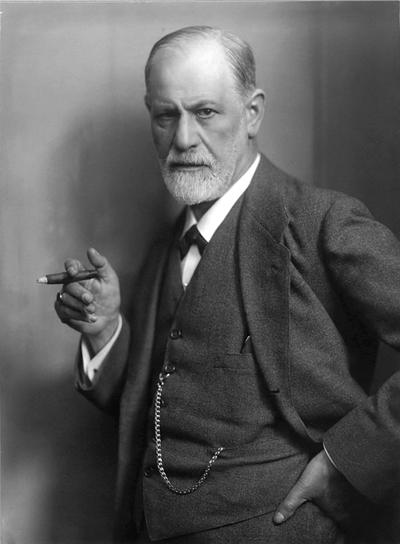

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud[2†]

Sigmund Freud[2†]Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the pioneer of psychoanalysis, a method for treating psychological issues rooted in unconscious conflicts. His theories, including the id, ego, super-ego, and the Oedipus complex, revolutionized the understanding of the human mind and its development. Freud’s work on dream analysis, libido, and the death drive has deeply impacted psychology and culture, despite ongoing criticism and debate about its scientific validity and implications. His contributions earned him the title "father of modern psychology"[1†][2†][3†].

Early Years and Education

Sigmund Freud was born on May 6, 1856, in Freiberg, Moravia, Austrian Empire (now Příbor, Czech Republic)[1†][4†]. He was the first child of his father’s third marriage. His father, Jakob Freud, was a Jewish wool merchant, and his mother, Amalia Nathanson, was nineteen years old when she married Jakob, who was then thirty-nine[1†][4†]. Sigmund’s two stepbrothers from his father’s first marriage were approximately the same age as his mother, and his older stepbrother’s son, Sigmund’s nephew, was his earliest playmate[1†][4†].

In 1859, the Freud family moved to Leipzig for economic reasons, and then a year later to Vienna, where Freud lived until the Nazi annexation of Austria 78 years later[1†]. Freud’s early experience was that of an outsider in an overwhelmingly Catholic community. However, Emperor Francis Joseph had liberated the Jews of Austria, giving them equal rights and permitting them to settle anywhere in the empire[1†][4†].

Freud attended the local elementary school, then the Sperl Gymnasium in Leopoldstadt, from 1866 to 1873[1†][4†]. He studied Greek and Latin, mathematics, history, and the natural sciences, and was a superior student[1†][4†]. He passed his final examination with flying colors, qualifying to enter the University of Vienna at the age of seventeen[1†][4†].

Freud enrolled in medical school in 1873[1†][4†]. Vienna had become the world capital of medicine, and the young student was initially attracted to the laboratory and the scientific side of medicine rather than clinical practice[1†][4†].

Career Development and Achievements

After earning his medical degree, Freud began practicing as a doctor in Vienna[3†]. He was appointed Lecturer on Nervous Diseases at the University of Vienna in 1885[3†]. His interest in the human mind was piqued after attending lectures given by the French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot in Paris[3†][5†]. This would later influence his work in psychoanalysis[3†].

Freud’s early career was marked by his collaboration with Josef Breuer in treating hysteria through the recall of painful experiences under hypnosis[3†][5†]. However, the Viennese medical community rejected the ideas he brought back from Paris, specifically on what was then called hysteria[3†]. This led Freud to withdraw from academia[3†].

Despite this setback, Freud continued to make significant contributions to neurology. He published influential works such as “On Aphasia: A Critical Study,” in which he coined the term agnosia, meaning the inability to interpret sensations[3†]. Freud and Breuer also published “Preliminary Report” and “Studies on Hysteria.” After their friendship ended, Freud continued to publish his own works on psychoanalysis[3†].

Freud’s most notable contribution to psychology is the development of psychoanalysis[3†][1†][3†]. This clinical method for treating mental disorders posits that such conditions might be caused purely by psychological rather than organic factors[3†][6†]. Freud’s theories on the structure of the subconscious, human sexual activity, repression, and defense mechanisms have significantly influenced our understanding of the human mind[3†][1†][3†].

Freud’s work laid the foundation for many other theorists to formulate ideas, while others developed new theories in opposition to his ideas[3†]. Despite the controversies surrounding his theories, Freud’s influence on psychology and related fields remains substantial, earning him the title of "father of modern psychology"[3†].

First Publication of His Main Works

Sigmund Freud was a prolific writer, publishing more than 320 different books, articles, and essays[7†]. Here are some of his most significant works:

- Preliminary Report (1893, co-authored with Josef Breuer): This early collaborative work between Freud and Breuer provided initial insights into the treatment of hysteria and introduced the concept of the talking cure[7†].

- Studies on Hysteria (1895): Co-authored by Freud and his colleague Josef Breuer, this book described their work and study of a number of individuals suffering from hysteria, including one of their most famous cases, a young woman known as Anna O[7†]. “Studies on Hysteria” is significant because it introduced the use of psychoanalysis as a treatment for mental illness[7†].

- The Interpretation of Dreams (1900): This book, which Freud often identified as his personal favorite, lays out his theory that dreams represent unconscious wishes disguised by symbolism[7†]. It served as a foundational text for his theories of psychoanalysis, laying out many of his ideas on the unconscious, dream interpretation, and the meaning of latent and manifest dream content[7†].

- Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901): This book takes a closer look at many deviations that occur during everyday life, including forgetting names, slips of the tongue (aka Freudian slips), and errors in speech and concealed memories[7†]. Freud analyzes the underlying psychopathology that he believed led to such errors[7†].

- Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious (1905): Freud analyzed humor and its psychological functions, suggesting that jokes reveal repressed thoughts and desires[7†].

- Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality or Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex (1905): This work is considered one of Freud’s most important. In it, he postulated the existence of libido, an energy with which mental processes and structures are invested and which generates erotic attachments, and a death drive, the source of compulsive repetition, hate, aggression, and neurotic guilt[7†][1†].

- Delusion and Dream (1909): Freud examined the similarities between delusions and dreams, analyzing their psychological functions and underlying mechanisms[7†].

- Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood (1910): Freud provided a psychoanalytic interpretation of Leonardo da Vinci’s life and work, exploring the impact of early experiences on his creativity[7†].

- The Origins of Psycho-analysis (1910): This collection of lectures and writings offered insights into Freud's early development of psychoanalytic theory[7†].

- Five Lectures on Psycho-Analysis (1910): This series of lectures provided an accessible introduction to Freud’s theories of psychoanalysis for a broader audience[7†].

- Totem and Taboo (1913): Freud applied psychoanalytic theory to primitive cultures, proposing that totemism and taboo systems reflect the Oedipus complex[7†].

- From the History of an Infantile Neurosis (1918): Freud presented a detailed case study of a patient's childhood neurosis, illustrating his theories on psychosexual development and childhood trauma[7†].

- The Uncanny (1919): Freud analyzed the concept of the uncanny, exploring how certain experiences evoke a sense of eeriness and fear, often due to repressed or unconscious elements[7†].

- Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920): This publication introduced the death drive (Thanatos) alongside the pleasure principle, expanding Freud's theories to include destructive impulses[7†].

- Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1921): Freud explored the influence of group dynamics on individual psychology and the role of the ego within social contexts[7†].

- The Ego and the Id (1923): Freud detailed his structural model of the psyche, describing the roles of the id, ego, and superego in human behavior[7†].

- Inhibitions, Symptoms and Anxiety (1926): Freud explored the interplay between inhibitions, symptoms, and anxiety, focusing on how these elements manifest in neurotic disorders[7†].

- The Future of an Illusion (1927): Freud examined religion as an illusion, arguing that it is a product of human psychological needs and wishes[7†].

- Civilization and Its Discontents (1930): Freud examined the inherent conflict between individual desires and societal expectations, arguing that civilization imposes constraints that lead to dissatisfaction[7†].

- An Outline of Psychoanalysis (1938): Freud provided a concise overview of psychoanalytic theory, detailing concepts such as the unconscious, defense mechanisms, and psychosexual development[7†].

- Moses and Monotheism (1939): Freud analyzed the origins of monotheism and proposed that Moses was an Egyptian prince, offering a psychoanalytic interpretation of religious history[7†].

These works were not only pivotal in the development of psychoanalytic theory but also had a profound impact on the field of psychology and beyond[7†][1†].

Analysis and Evaluation

Sigmund Freud’s theories and contributions to psychology have been influential, yet they have also been the subject of considerable debate and criticism[8†][9†].

Freud’s psychoanalytic approach sought to explore the unconscious mind to uncover repressed feelings and interpret deep-rooted emotional patterns[8†][9†]. He believed that events in our childhood have a great influence on our adult lives, shaping our personality[8†]. For example, anxiety originating from traumatic experiences in a person’s past is hidden from consciousness and may cause problems during adulthood[8†]. Freud’s life work was dominated by his attempts to penetrate this often subtle and elaborate camouflage that obscures the hidden structure and processes of personality[8†].

Freud introduced several influential concepts, including the Oedipus complex, dream analysis, and the structural model of the psyche divided into the id, ego, and superego[8†]. His lexicon has become embedded within the vocabulary of Western society[8†]. Words he introduced through his theories are now used by everyday people, such as anal (personality), libido, denial, repression, cathartic, Freudian slip, and neurotic[8†].

However, Freud’s theories have also been criticized. Some critics argue that his theories are more pseudoscientific than scientific, as they lack empirical evidence and are not falsifiable[8†][9†]. Others argue that Freud’s theories are sexist, as they often portray women as inferior to men[8†][9†].

Despite these criticisms, Freud’s influence on psychology and related fields remains significant. His theories have shaped the way we think about the human mind and behavior, and they continue to spark debate and inspire research[8†][9†].

Personal Life

Sigmund Freud was an intensely private man[4†]. He was born as the first child of his twice-widowed father’s third marriage[4†]. His mother, Amalia Nathanson, was nineteen years old when she married Jacob Freud, aged thirty-nine[4†]. Sigmund’s two stepbrothers from his father’s first marriage were approximately the same age as his mother, and his older stepbrother’s son, Sigmund’s nephew, was his earliest playmate[4†]. Thus, the boy grew up in an unusual family structure, his mother halfway in age between himself and his father[4†]. Though seven younger children were born, Sigmund always remained his mother’s favorite[4†].

In 1886, Sigmund married Martha Bernays, who was the granddaughter of the chief rabbi of Hamburg, Isaac Bernays[4†][10†]. Sigmund and Martha had six children between 1887 and 1895[4†][10†]. There were also unconfirmed rumors that Sigmund had a romantic relationship with Martha’s sister, Minna Barneys[4†][10†].

Freud read extensively, loved to travel, and was an avid collector of archeological oddities[4†]. He was devoted to his family, and he always practiced in a consultation room attached to his home[4†].

Conclusion and Legacy

Sigmund Freud’s work has had an enduring impact on psychology and related fields[11†][12†][13†][14†]. His theories have become so commonplace that they are intertwined in our belief systems[11†]. Many of the terms which he developed have become an integral part of social discourse[11†]. For example, the term a “Freudian slip” is often used in conversation when someone says something that may be termed a mistake, but in essence, Freud would state that the slip was not a mistake at all, but is based on the unconscious mind revealing what the person may truly feel or think[11†].

Freud’s single greatest insight was that most of what goes on in the mind is hidden from our conscious view[11†][14†]. He taught us that the conscious self is the result of a complex interplay of subterranean forces[11†][14†]. His theories have either evolved or been supplanted by other theories, but his impact on society at large remains significant[11†].

Freud’s scientific legacy has implications for a wide range of domains in psychology, such as integration of affective and motivational constraints into connectionist models in cognitive science[11†][12†]. Despite all the fuss about him over the years, he has hardly ever been really popular or taken seriously[11†]. Most people think he is mad and sex-obsessed, and the modern-day scientific establishment haughtily dismisses him as a charlatan and fanciful[11†]. None of them can cope with his unerring insistence on the power and complexity of human emotions and on the sheer abundance of irrationality in our everyday lives[11†].

Despite these debates, Freud’s influence on psychology and related fields remains significant[11†]. His work has generated extensive and highly contested debate concerning its therapeutic efficacy, its scientific status, and whether it advances or hinders the feminist cause[11†]. Nevertheless, he made a tremendous impact on society at large[11†].

Key Information

- Also Known As: Sigismund Schlomo Freud[1†][3†]

- Born: May 6, 1856, Freiberg, Moravia, Austrian Empire (now Příbor, Czech Republic)[1†][3†]

- Died: September 23, 1939, London, England[1†][3†]

- Nationality: Austrian[1†][3†]

- Occupation: Neurologist, Founder of Psychoanalysis[1†][3†]

- Notable Works: Freud’s theories, including those about the id, ego, and super-ego, the Oedipus complex, repression, defense mechanisms, and stages of psychosexual development, have had a profound impact on the field of psychology[1†][3†].

- Notable Achievements: Freud’s creation of psychoanalysis was a significant milestone that led to a new understanding of the human mind. His work continues to generate extensive and highly contested debate concerning its therapeutic efficacy, its scientific status, and whether it advances or hinders the feminist cause[1†][3†].

References and Citations:

- Britannica - Sigmund Freud: Austrian psychoanalyst [website] - link

- Wikipedia (English) - Sigmund Freud [website] - link

- Verywell Mind - Sigmund Freud's Life, Theories, and Influence [website] - link

- Encyclopedia of World Biography - Sigmund Freud Biography [website] - link

- BBC History - Historic Figures - Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) [website] - link

- Britannica - Sigmund Freud and his contribution to psychoanalysis [website] - link

- Verywell Mind - Influential Books by Sigmund Freud [website] - link

- Simply Psychology - Sigmund Freud: Theory & Contribution to Psychology [website] - link

- Simply Psychology - Psychoanalysis: Freud's Psychoanalytic Approach to Therapy [website] - link

- Totallyhistory.com - Sigmund Freud Biography - Life of Austrian Psychologist [website] - link

- The Guardian - The enduring legacy of Sigmund Freud, radical [website] - link

- APA PsycNet - APA PsycNet [website] - link

- Philosophy Talk - The Legacy of Freud [website] - link

- Philosophy Talk - The Legacy of Freud [website] - link

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; additional terms may apply.

Ondertexts® is a registered trademark of Ondertexts Foundation, a non-profit organization.