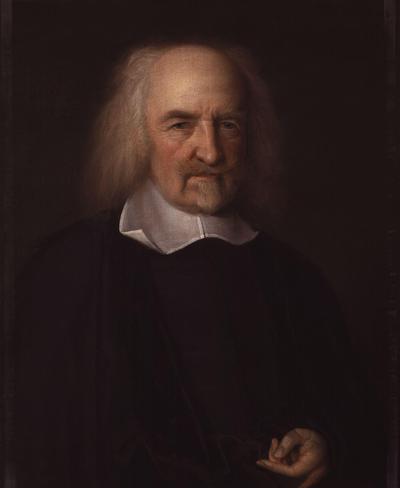

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes[2†]

Thomas Hobbes[2†]Thomas Hobbes (April 5, 1588 - December 4, 1679) was an influential English philosopher, best known for his work in political philosophy[1†][2†]. His most notable work, “Leviathan” (1651), is a cornerstone of Western political philosophy and social contract theory[1†][2†].

Early Years and Education

Thomas Hobbes was born on April 5, 1588, in Westport, Wiltshire, England[1†][2†]. His father was a vicar of a small parish church, who, after engaging in a brawl at his own church door, disappeared and left his three children to the care of his brother, a well-to-do glover in Malmesbury[1†]. Hobbes’s early life was thus marked by a significant absence of parental guidance.

Hobbes began his education at the age of four at Westport church, then moved to a private school, and finally, at the age of 15, he attended Magdalen Hall in the University of Oxford[1†]. Here, he took a traditional arts degree and developed an interest in maps[1†]. His intellectual curiosity was evident even in these early years, setting the stage for his later contributions to various fields of study.

For nearly his entire adult life, Hobbes worked for different branches of the wealthy and aristocratic Cavendish family[1†]. Upon completing his degree at Oxford in 1608, he was employed as a page and tutor to the young William Cavendish, who would later become the second earl of Devonshire[1†]. This relationship with the Cavendish family provided Hobbes with the stability and resources to pursue his intellectual interests.

Hobbes’s early years and education were thus characterized by a mix of adversity and opportunity. Despite the challenges he faced, his intellectual curiosity and determination set the foundation for his later achievements as one of the most influential philosophers of his time.

Career Development and Achievements

Thomas Hobbes’s career was marked by his work as a philosopher, scientist, and historian[1†][2†]. His most significant contribution is his political philosophy, particularly as articulated in his masterpiece, “Leviathan” (1651)[1†][2†]. In “Leviathan”, Hobbes expounded an influential formulation of social contract theory[1†][2†]. He viewed government primarily as a device for ensuring collective security[1†]. Political authority, according to Hobbes, is justified by a hypothetical social contract among the many that vests in a sovereign person or entity the responsibility for the safety and well-being of all[1†].

In addition to his political philosophy, Hobbes made substantial contributions to a diverse array of fields, including history, jurisprudence, geometry, theology, and ethics[1†][2†]. He is often credited with justifying wide-ranging government powers based on the self-interested consent of citizens[1†].

Hobbes was not only a scientist in his own right but also a great systematizer of the scientific findings of his contemporaries, including Galileo Galilei and Johannes Kepler[1†]. His scientific writings present all observed phenomena as the effects of matter in motion[1†].

Hobbes’s other major works include “De Cive” (1642), “De Corpore” (1655), and “De Homine” (1658), as well as the posthumous work “Behemoth” (1681)[1†][2†]. Each of these works further illustrates Hobbes’s extensive intellectual contributions across various fields.

Hobbes’s career was also marked by his role as a tutor to the Cavendish family[1†][2†]. This relationship provided him with the stability and resources to pursue his intellectual interests[1†].

Hobbes’s career achievements thus span a wide range of fields, reflecting his intellectual curiosity and commitment to understanding the world around him. His work continues to influence contemporary philosophy and our understanding of political structures and authority.

First Publication of His Main Works

Thomas Hobbes’s philosophical contributions spanned various fields, but he is most renowned for his works in political philosophy. Here are some of his main works:

- Leviathan, or the Matter, Form, and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiastical and Civil (1651)[4†]: This is Hobbes’s masterwork, published in 1651. It contains four parts: “Of Man,” “Of Commonwealth,” “Of a Christian Commonwealth,” and “Of the Kingdom of Darkness.” “Of Man” connects Hobbes’s understanding of human nature with his views on societal structure[4†].

-

The Elements of Philosophy: This work is composed of three parts, not published in their intended order[4†].

- De Corpore (1655)[4†]: Published in 1655, it contains four parts. Part I concerns logic, Part II concerns scientific concepts, Part III concerns geometry and mathematics, and Part IV presents Hobbes’s views on human nature[4†].

- De Homine (1658)[4†]: Published in 1658, it opens with ten chapters on optics. The last five chapters treat Hobbes’s accounts of the passions and an analysis of the origins of religion[4†].

- De Cive (1642)[4†]: Published in 1642, it was Hobbes’s first definitive articulation of his political philosophy. It includes Hobbes’s account of the state of nature and the origin of society[4†].

- The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic (1640)[4†]: This is Hobbes’s first published philosophical work, which was written in part in response to the conflicts between Charles I and Parliament[4†].

- Of Liberty and Necessity and Selections from Questions concerning Liberty, Necessity, and Chance (1654-1656)[4†]: This volume presents an exchange between Hobbes and the Anglican cleric John Bramhall. They debate questions such as whether human beings can act freely, what freedom means, whether freedom and material determination can coexist, and how divine punishment can be justified[4†].

- A Dialogue between a Philosopher and a Student of the Common Laws of England (written 1666, published 1681)[4†]: Hobbes presents here, in dialogue form, a reflection on the relation between reason and law[4†].

- Behemoth, or the Long Parliament (written 1668, published 1682)[4†]: Behemoth is Hobbes’s account of the English Civil Wars of the 1640s[4†].

These works collectively present Hobbes’s views on a wide range of topics, including human nature, societal structure, liberty, necessity, and the nature of law. They continue to be influential in various fields of philosophy.

Analysis and Evaluation

Thomas Hobbes’s philosophical contributions have had a profound impact on Western political thought[5†][6†]. His works, particularly “Leviathan,” present a grim picture of human nature and the state of nature, which Hobbes famously described as "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short"[5†][7†]. He argued that in the state of nature, there is a “war of every man against every man,” with individuals constantly seeking to destroy one another[5†][8†].

Hobbes’s political philosophy is grounded in his materialist view of human nature and the world[5†]. He believed that fear and power play a crucial role in human relations[5†][6†]. This led him to advocate for a strong central authority or an “absolute monarchy” as the best form of government[5†]. According to Hobbes, such a government is necessary to maintain order and prevent the state of nature, which he viewed as a state of perpetual war[5†][7†].

His views on liberty and necessity, as discussed in his exchange with John Bramhall, also offer valuable insights into his philosophical thought[5†][4†]. They debated questions such as whether human beings can act freely, what freedom means, whether freedom and material determination can coexist, and how divine punishment can be justified[5†][4†].

Hobbes’s works have been subject to extensive analysis and critique. His depiction of the state of nature and his justification for absolute monarchy have been particularly controversial. Despite the debates surrounding his ideas, Hobbes’s influence on political philosophy is undeniable[5†][6†].

Personal Life

Thomas Hobbes was born on April 5, 1588, in Westport, now part of Malmesbury in Wiltshire, England[2†]. His father, a vicar of a small Wiltshire parish church, was quick-tempered and after engaging in a brawl at his own church door, he disappeared, abandoning his three children[2†][1†]. Hobbes was left in the care of his uncle, a well-to-do glover in Malmesbury[2†][1†].

Hobbes had a brother, Edmund, about two years older, and a sister, Anne[2†]. Although much of Hobbes’s childhood is unknown, it is known that he was sent to school at Westport, then to a private school, and finally, at 15, to Magdalen Hall in the University of Oxford[2†][1†].

For nearly his entire adult life, Hobbes was employed by members of the wealthy and aristocratic Cavendish family and their associates as a tutor, translator, traveling companion, keeper of accounts, business representative, political adviser, and scientific collaborator[2†][1†].

While Hobbes was born and died in England, he spent approximately a decade of his life in exile in Paris between 1640 and 1651[2†][9†]. This was in regards to the civil wars that were occurring at the time[2†][9†].

Conclusion and Legacy

Thomas Hobbes, born on April 5, 1588, in Westport, Wiltshire, England, and died on December 4, 1679, in Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire, was an English philosopher, scientist, and historian[1†]. He is best known for his political philosophy, especially as articulated in his masterpiece “Leviathan” (1651)[1†].

Hobbes’s enduring contribution is as a political philosopher who justified wide-ranging government powers on the basis of the self-interested consent of citizens[1†]. He viewed government primarily as a device for ensuring collective security[1†]. Political authority, according to Hobbes, is justified by a hypothetical social contract among the many that vests in a sovereign person or entity the responsibility for the safety and well-being of all[1†].

Hobbes was not only a scientist in his own right but a great systematizer of the scientific findings of his contemporaries, including Galileo and Johannes Kepler[1†]. His scientific writings present all observed phenomena as the effects of matter in motion[1†].

Hobbes believed that traditional philosophy had never been able to reach irrefutable conclusions or secure universal truth and that this failure was the cause not only of philosophical controversy but also of civil discord and even civil war[1†][6†].

According to Hobbes, the political legacy of his notion on the state is to protect citizens by creating security, order, commerce, and other services that are necessary for successful running of the state[1†][10†].

Key Information

- Also Known As: Unknown

- Born: Thomas Hobbes was born on April 5, 1588, in Westport, Wiltshire, England[1†][2†].

- Died: He died on December 4, 1679, in Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire, England[1†][2†].

- Nationality: English[1†][2†].

- Occupation: Philosopher, scientist, and historian[1†][2†].

- Notable Works: His most notable work is “Leviathan” (1651), in which he expounded an influential formulation of social contract theory[1†][2†]. Other major works include “De Cive” (1647), “De Corpore” (1655), and “Behemoth” (1681)[1†][2†].

- Notable Achievements: Hobbes is best known for his political philosophy, especially as articulated in his masterpiece “Leviathan” (1651). He viewed government primarily as a device for ensuring collective security[1†][2†]. He justified wide-ranging government powers on the basis of the self-interested consent of citizens[1†][2†].

References and Citations:

- Britannica - Thomas Hobbes: English philosopher [website] - link

- Wikipedia (English) - Thomas Hobbes [website] - link

- Great Thinkers - Biography - Thomas Hobbes [website] - link

- Great Thinkers - Major Works - Thomas Hobbes [website] - link

- SparkNotes - Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679): Study Guide [website] - link

- SparkNotes - Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679): Background on Thomas Hobbes and Leviathan [website] - link

- UKEssays - The Analysis Of Thomas Hobbes And The Government Philosophy Essay [website] - link

- SparkNotes - Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679): Full Work Summary [website] - link

- History-Computer - Thomas Hobbes [website] - link

- WOWESSAYS™ - Essays About What Has Been The Political Legacy Of Hobbess Notion Of The State [website] - link

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0; additional terms may apply.

Ondertexts® is a registered trademark of Ondertexts Foundation, a non-profit organization.